| Selo & Selochrome Film |

|

|

|

|

|

The Chemist and Druggist magazine, 29th March 1930 |

||||

|

||||

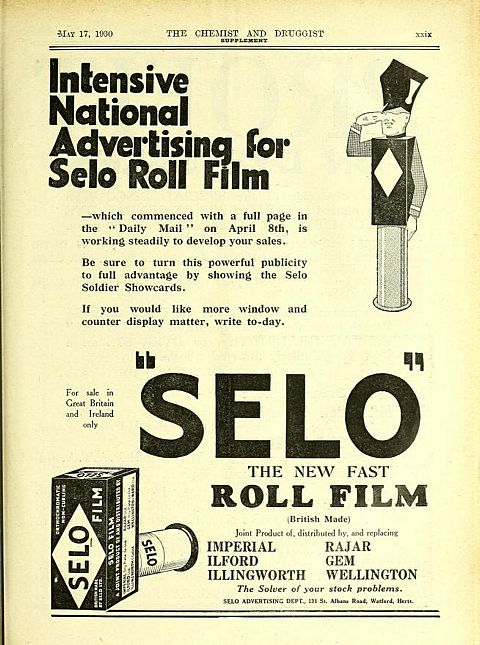

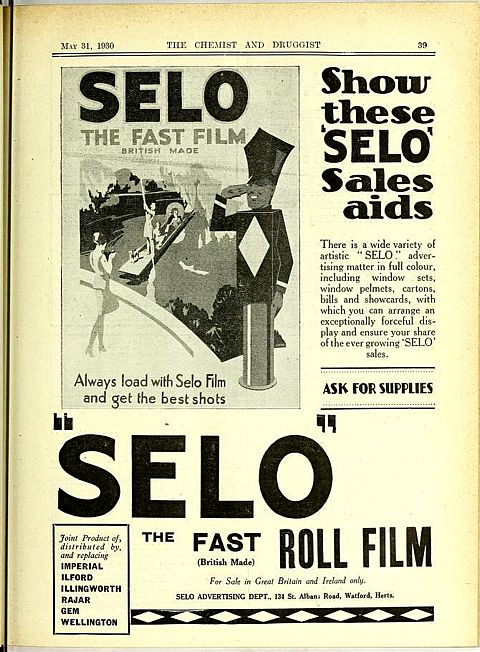

| The Chemist and Druggist magazine, 17th May 1930 | The Chemist and Druggist magazine, 31st May 1930 | |||

|

|

|||

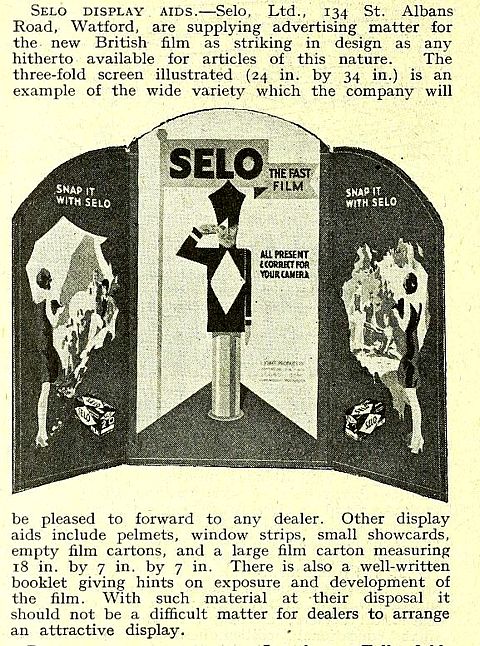

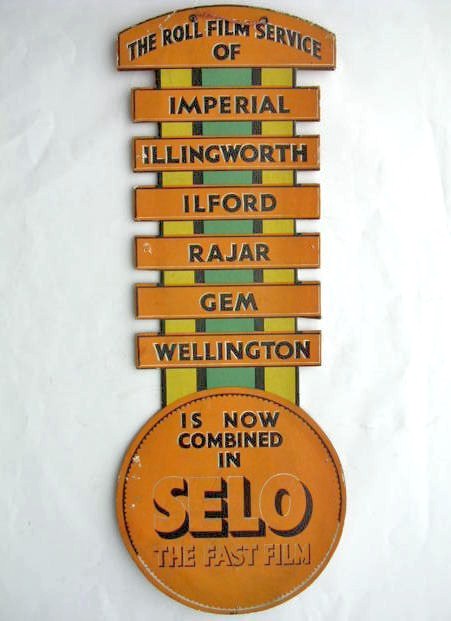

| Taken from the Chemist and Druggist magazine, 26th April 1930, p512 | Below: An advertising sign showing the six film manufacturing companies who combined, under Ilford, to market Selo Roll Film from 8th April 1930. | |||

|

|

|||

| Below taken from Amateur Photographer magazine, 10th September 1930 | ||||

|

||||

| To download the leaflet below (believed to date to mid-1931) as a pdf, click here or on the image. | ||||

|

|

||||

| Below: An Ilford advert for Selo film taken from the 1944 BJPA | ||||

|

||||

|

ILFORD films prior to Selo Before the formal Selo announcement in spring 1930, the 1930 British Journal of Photography Almanac (BJPA), which contained advertisements for goods and equipment available prior to the end of 1929, contained the Ilford advertisement shown to the right.

It's possible that 'Ilford Roll Film', speed H&D 350, is the film that became the first of the Selo films. |

|

|||

| Below are descriptions of visits to the SELO factory, in 1931 (Kinematograph Society) and in 1945 (Meccano Magazine). | ||||

|

Kinematograph Society

Visit Selo Works (1931) The company in groups under different guides made a prolonged and exhaustive tour of the company's works. Every process was illustrated and explained, from the first handling of the raw material through the coating, testing and cutting processes, down to the final machine which cartons the finished product. With one minor exception, every machine in the place is of British manufacture. The works impressed every visitor by the orderliness of their layout and the extreme cleanliness evident in every detail. To talk of a spotless factory, especially one on so large a scale as this, is commonly a misuse of words, but in this case scrubbed woodwork, paint, washed and oiled floors and a comprehensive system of air-conditioning, makes the factory in its entirety as clean as a hospital operating room. What was rather surprising was to find the high degree of illumination possible nowadays in such departments as the perforating room, where an immense battery of Bell & Howell perforators is installed. A few years ago this operation would have had to be carried out in almost complete darkness, whereas today the employment of modern filters makes it possible to read news-print without difficulty. The Selo factory can, without exaggeration, be called a model of efficiency. Incredible pains are taken to ensure uniformity in emulsion and a minimum of human dust raising movement in manufacturing processes, and a system of inspection and regular laboratory tests at each stage result in a quality and speed of emulsion that is now freely acknowledged by trade workers to be above criticism. The cinematograph section of the business has been unavoidably the last to be developed, but the plant in this connection is now being tripled and should be in full production during the next fortnight. Evidently the Selo people intend to be in a position to take full advantage of any improvement in the British trading position from now on, and they regard the future as full of hope. Enthusiastic votes of thanks to the company and staff especially the genial works manager, L.F.Davidson, ended a memorable visit. |

||||

| From The Meccano Magazine; HOW THINGS

ARE MADE: Ilford Selo Films (1945) "Can I have your matches or cigarette lighter, Sir?" This request by the gatekeeper at the Ilford Selo Works brought me up with a jerk. Was I in a danger zone? Then I remembered that photographic films are coated on celluloid and celluloid is highly inflammable, so anything likely to cause a spark or flame is rigorously excluded from the factory. I handed over my lighter, donned a white coat reaching down to my ankles, and a hat, something like a chef's, which pulled dowm to the back of my skull, completely covering my hair. This, I was told, was a precautionary measure to minimise the risk of dust being carried to the coating rooms. The great factory which I was about to enter houses a plant capable of producing, in a single day, many miles of film, using a considerable quantity of silver nitrate in so doing. Hundreds of men and women are employed here, many of them skilled chemists and physicists, and all of them highly experienced in their particular branch of work. |

||||

|

|

|||

|

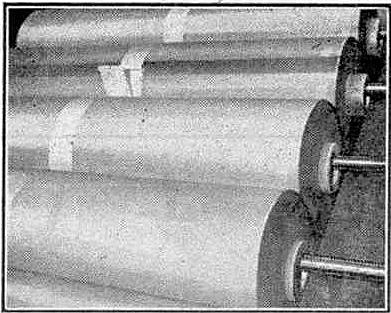

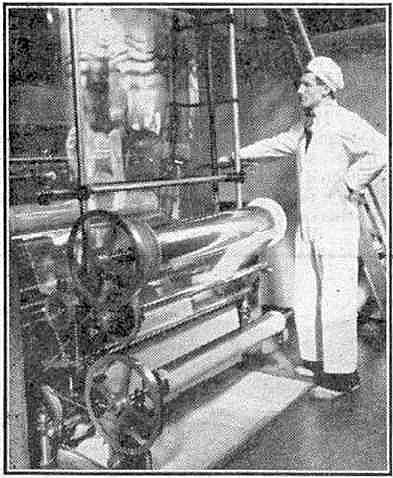

On entering the factory the first thing that impresses the visitor is the absence of noise and bustle. Everything seems to be planned to eliminate waste of time and effort, as indeed it is. Everywhere there is a continual war against dust and atmospheric impurities, and a standard of cleanliness exists which would make the most house-proud wife in Britain sigh with envy and despair. I was taken first to the celluloid store, where I saw huge rolls of this material (above, left) which generates electricity on its own account if slightly rubbed, and I quickly realised the force of the gatekeeper's request. Only a limited quantity of celluloid is permitted to be housed in one store, and in each store the walls and ceilings are fireproof, with sprinklers overhead which automatically, at a given temperature such as would be present in the case of fire, let down a deluge of water sufficient to drench everything beneath. Seen in rolls celluloid has the appearance of polished silver; spread out it looks like flexible glass. I went on to see the base made ready for coating with emulsion. This operation consists of running the celluloid over rollers which deposit a chemical substance to form a bond between the gelatine coating and the celluloid. Subsequently both sides of the celluloid are coated with gelatine to make it lie flat and prevent curl when it is cut up into roll film camera sizes. Meanwhile constant watch is kept to detect flaws in the celluloid so that these can be eliminated when the coated film is cut up. The 'subbing' (see above, right) of the base may take place some weeks before the final coating with the sensitive emulsion. In the meantime it is stored in dust-free rooms to "ripen" into the necessary condition. |

||||

|

|

|||

|

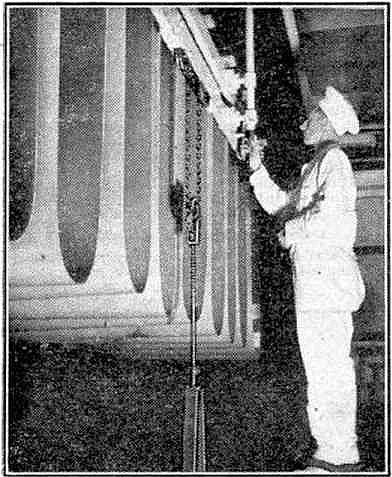

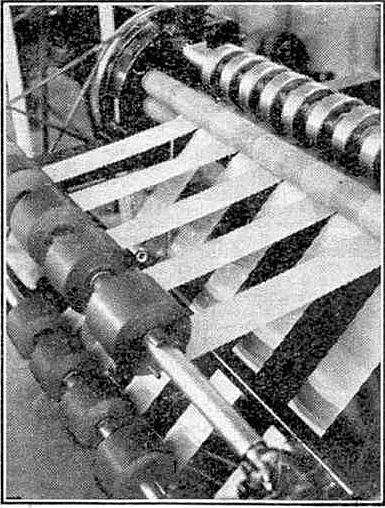

The making of photographic emulsions is done in a "safe" light and is a highly skilled process performed by trained laboratory assistants under the charge of experienced chemists. The constituents vary according to the type of emulsion, but fundamentally a photographic emulsion consists of silver nitrate added to a solution of gelatine containing an alkaline halide, which might be either bromide, chloride or iodide. Very roughly, and very briefly, the procedure is to swell the gelatine by prolonged soaking in cold water, then to dissolve it by heating, afterwards adding the alkaline halide and silver nitrate. The proportions of the various chemicals again vary according to the degree of sensitivity and contrast of the emulsion. The emulsification of the silver halide in gelatine is an intricate operation and must be very carefully carried out to ensure the uniform production of material of the requisite quality. The formulae and details of manufacturing operations are never divulged, as these, of course, are rightly regarded as trade secrets. After mixing the emulsions are "ripened" by heating in huge boilers. In many respects the emulsion-making laboratories may be likened to big cookhouses, indeed, emulsions are spoken of as being "cooked". Finally, after chilling, any soluble substances are removed by shredding in compressed air machines and washing in cold water, after which the emulsions go into cold storage to await a call from the coating rooms. When this comes an appropriate quantity is melted down to a suitable consistency for coating on to the already prepared celluloid. The coating rooms, where the emulsions are spread on to the celluloid, are perhaps the most intriguing from the visitor's point of view. From now on until after the film is cut and spooled the journey proceeds in almost complete darkness. Entering the coating room the guide considerately takes the visitor's hand and pilots him along what seems to be a long passage. Presently a stop is made alongside a machine and, as the eyes get accustomed to the darkness, a great band of celluloid is seen feeding into the machine, which distributes the emulsion carefully and uniformly on to the surface of the celluloid. The band passes on over a suction box which pulls it taut and then allows it to drop into a loose 'festoon' (see above, left). Here one expects the coated celluloid to fall to the ground, but along comes a stick moving on an endless chain, and suddenly rising, it lifts up the celluloid to the full height of its arm. The slack celluloid in front falls into loops about eight feet deep and passes on. Sticks continually rise and fall and new loops are formed, which travel on without ceasing to the end of their journey-and a very long journey it seems to be. The drying tracks are several hundred feet long and are divided into a series of bays, through which the coated film passes slowly. As the film travels along the track the temperature changes from very cold (which sets the emulsion), gradually warming up in each successive bay, then cooling down to normal at the reeling end of the track. The newly coated film is now at the end of its journey, dry, perfect and ready for cutting up. The hundreds of sticks which carry the film along in the festoons are meanwhile returning to their starting place to take up another load of loops. Throughout its long journey the coated film is untouched by human hands. Machinery serves the coating machines with emulsion and guides the celluloid to the coating troughs, pulling it taut for the coating operations and then picking the coated celluloid up and hanging it in symmetrical festoons. Machinery drives the film forward through the changing temperatures and rolls it up at the end of its journey, dry and ready for 'slitting' (see above. right) and cutting into roll film lengths. The wide band of film, after being reeled at the end of the drying track, goes on to a slitting machine which divides it into long lengths of suitable width. This machine comprises a series of pairs of circular knives which can be adjusted according to the width of film it is desired to cut. The strips are then cut into the appropriate camera lengths and backed with light-tight paper, the two being fastened together at a given position. Spooling is a hand operation, and a small army of girls wearing white gloves dexterously wind the film onto the spools. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Selochrome no longer manufactured after 1968) |

||||

|

The 127 size SELO roll film shown below must be one of the earliest Selo films produced following the 8th April 1930 film production announcement. Its expiry date is April 1932. No film speed is indicated. It was intended for snap-shot cameras with few adjustments, so film speed may have been intentionally omitted to avoid confusing its intended customers. It was possibly around 25 ASA (in the post-1960 speed rating system). The pictures below accompanied the ebay listing which this author won. |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

Selochrome (Ortho) roll film

with a 1942 expiry date.

Panchromatic film is much more evenly sensitive (akin to the eye) to all visible colours, but has to be handled in total darkness. |

|

|||

|

This film box is a 120 roll of SP (= Selochrome Panchromatic) 80ASA, 30ºBSI & Scheiner, 20ºDIN film. It passed its expiry date in June 1962. After 1960, Selochrome Pan was re-rated to 160ASA (no change in the emulsion). So this 80ASA example must have been manufactured and boxed just before that re-rating of the film speed took place. The change in packaging to a white coloured box, as the examples below, seemingly took place around 1965, when the new 'sunburst' trade mark was introduced. |

|

|||

| The pictures below

show a twin-pack of 127 size roll film, with an expiry date of

March 1969. These pictures

were sent to me by Leon Chipchase (in Aug 2024). One of the films has been exposed and the other is still in its opaque, green, sealed paper enclosure. |

||||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

|||

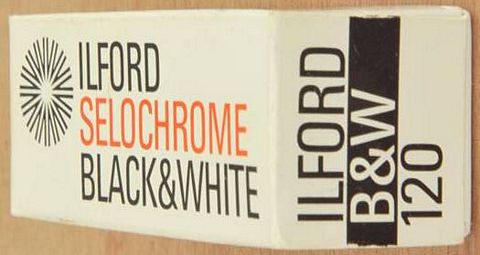

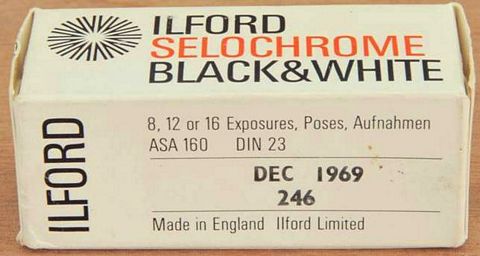

| An even later production Selochrome film than the one above, this being a 120 size Selochrome pan(chromatic) roll film carton showing an expiry date of December 1969. Images sent by Michael Talbert. | ||||

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

||||