|

Working while a Student at Johnsons of Hendon, 1965-1966 by John Spokes |

|

|

|

|

| Written by John Spokes |

|

INTRODUCTION I cannot recollect the name of the Department I was employed in, which was the same on both occasions, (it may have been Production Services), but my function was to carry out relatively simple tests on final products or intermediates. Typically, these involved measuring the water content of powders, such as glycin or metol, done by evaporating the water from a known weight of sample using an infra-red lamp, checking liquid densities using a hydrometer and measuring liquid pH. Another test was measuring the viscosities of liquids using various types of viscometers. How these tests proved anything I do not know because, unless the operative had made a catastrophic mistake in the manufacaturing process, these tests, which were not particularly accurate, indicated very little. The most challenging test was checking the efficacy of a developer for X-ray plates; a test used actual X-ray film and took about an hour of relatively intense labour. Operatives would deliver samples to be tested to the lab. Some operatives would get anxious if they had to wait long for their results, as testing was often a precursor to the next process step or a signal to start bottling chemicals. But I quickly got to know the priorities and usually took the results back personally and, in this way, quickly developed an acquaintance with many of the workers and an understanding of the various facilities. Test results were written on a small (approx. A5) duplicate machine-printed test record, which had to be time and date stamped by the responsible Production Chemist, a somewhat ritualistic process. I lived at home in Rickmansworth at this time and travelled to Hendon by a mixture of car lifts, trains and buses and occasionally I got to borrow a car. It was a relatively simple commute - 40 minutes by car, but 60 to 90 minutes by other means. Most days I ate in the Works Canteen and occasionally walked up to Hendon Central, partly for exercise and partly to do some shopping. |

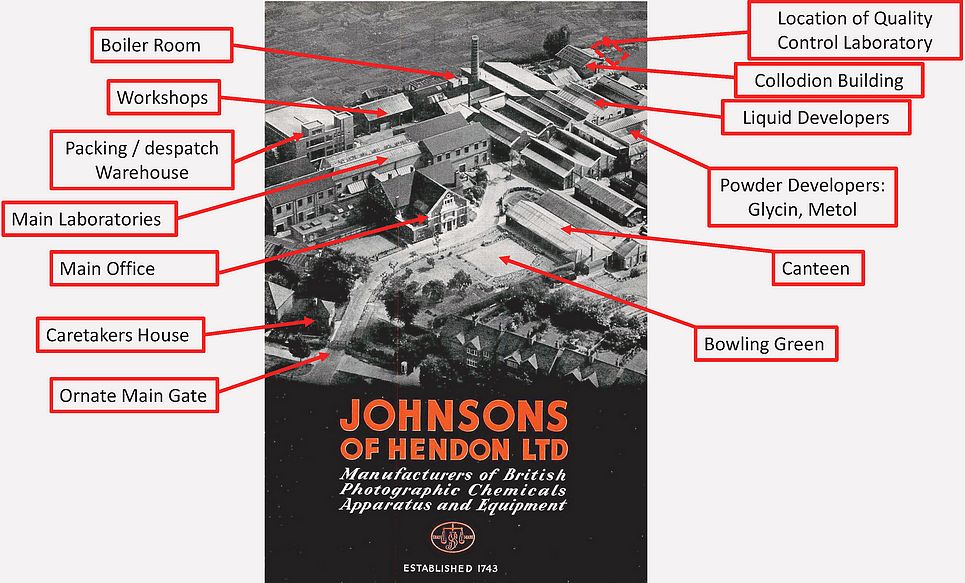

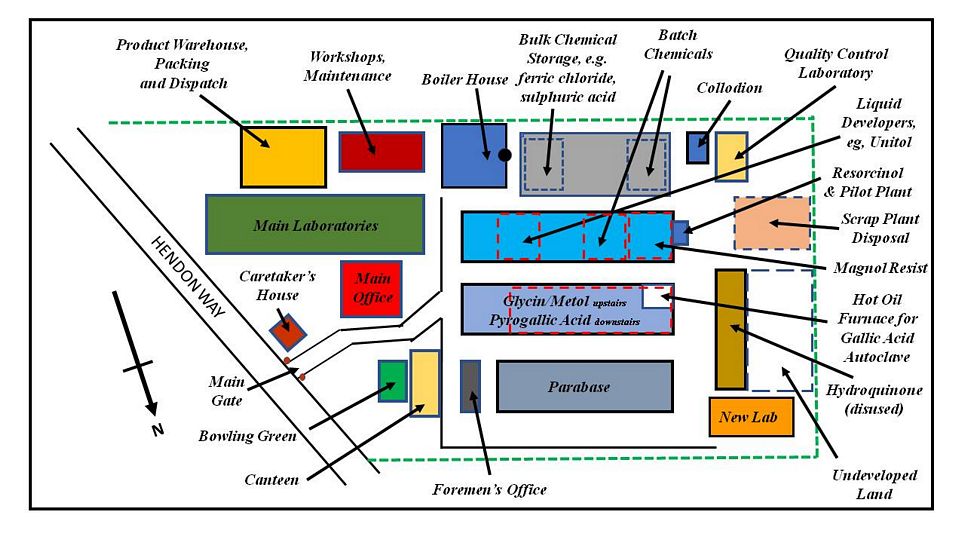

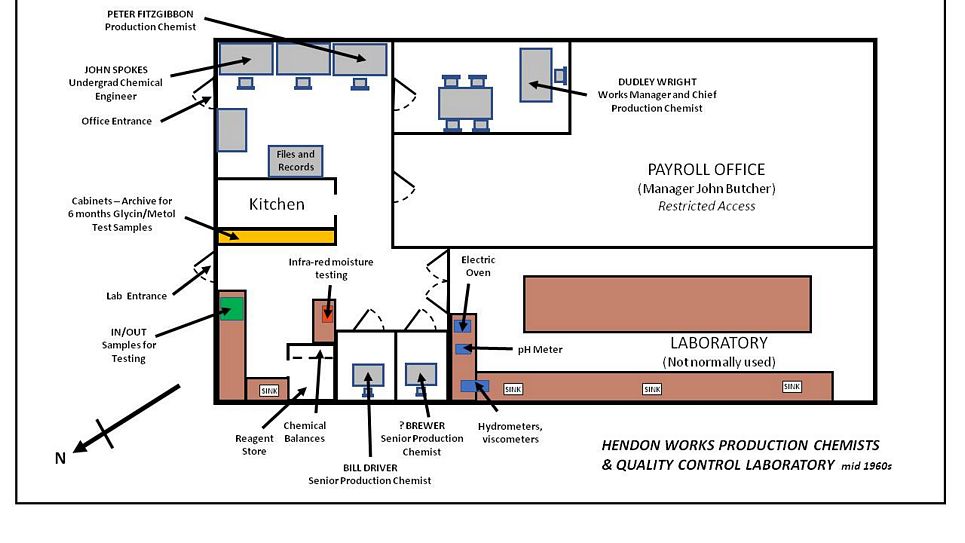

| THE FACILITIES The layout of the Hendon site is described and illustrated below by John, helped by his annotated diagrams. The aerial view is taken from the 1950 British Journal Almanac (BJPA) so doesn't correspond exactly to John's memories from the mid to late 1960s. John has produced his own site plan from his later memories. That image can be seen below the aerial view, together with a diagrammatic plan view from John, showing his recollections of the laboratory that he worked in. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The site was arranged approximately east-west and had begun in the east, adjacent Hendon Way, and expanded westwards (to the right in the picture) over the years. The site was entered from Hendon Way by a gateway with fancy brick gateposts adjacent to which was a house, within the works boundary, where I believe the site caretaker was resident. These brick gateposts were still existent in the early days of Brent Cross but are now gone. On entering the site, to the left were the original Main Office buildings, Laboratories and Warehousing. To the right was the works Canteen and, I think, the Occupational Health building, probably called the Medical Block in those days. Outside these, and opposite the entrance to the Main Office, was a large, pleasant, lawned area (marked Bowling Green on the view above. To the far left and a little further down the site were the Engineers' Offices and Workshops and the Boiler Room with two large oil-fired boilers, which were used primarily for steam heating in the various processes. There were many small buildings: offices, storerooms and laboratories in this original area and they were generally off-limits to me. What wasn't off-limits were the various production units contained mainly in four long double-storeyed buildings which ran from this initial office/lab area westward, down the site, for about 200 yards. The laboratory in which I worked was at the extremity of these buildings, to the south side. Adjacent this was a yard where old plant (much of it condemned) was stored and a single storey building where collodion was manufactured (see Collodion Building in the view above). This collodion process involved ether and cellulose nitrate, both nasty and the building was surrounded by a form of bund (embankment) to prevent surrounding buildings from any blast in the event of a fire and explosion. Access to this building was very restricted and in my whole time at Johnsons I visited it only twice. |

|

|

|

|

Our Chemists and Quality Control Laboratory (to the far south-west of the site, see John's diagrammatics above) was a single storey concrete pre-fab building with a small open plan office space, where I sat, and off this some small offices for the Production Manager and the more senior Production Chemists. There was a very small room for tea/coffee making, a large laboratory which was only partly used and had obviously formed part of a larger empire at one time and then the small testing lab area, which apart from sink and testing equipment, had floor-to-ceiling glass fronted cupboards full of small bottles containing dated samples of powder relating to production batches going back about 6 months. Typically, these sample bottles would contain glycin or metol. Part of the laboratory building was occupied by the small group who handled payroll and invoicing accounts - mostly done on Comptometer machines. At the other end of the site, adjacent the original main offices and labs, was a large Storage Warehouse and Packing area. This was mainly for products produced on site, but Johnsons were also agents for Voigtländer, Eumig and other photographic equipment manufacturers and these were stored in their hundreds on racks in this warehouse. Again, I visited these infrequently, but was very envious of some of the Voigtländer cameras all boxed-up. I had a Vito B at that time, one of the lesser models. Finally, at the far north-west corner of the developed site was a large, relatively new laboratory, but I'm not sure what this was used for, as I only visited it occasionally. (Editor's note: From my web page describing the work of Anthony 'Pip' Pippard, Chief Chemist from 1966 and Technical Director by 1970, this new (in 1966) laboratory may have been the base for Johnsons research into colour processing chemistries and may have been where early work was carried out that evolved into the very successful range of 'Photocolor' chemistries, later sold by Photo Technology Ltd after Hestair had closed the Hendon site.) |

|

|

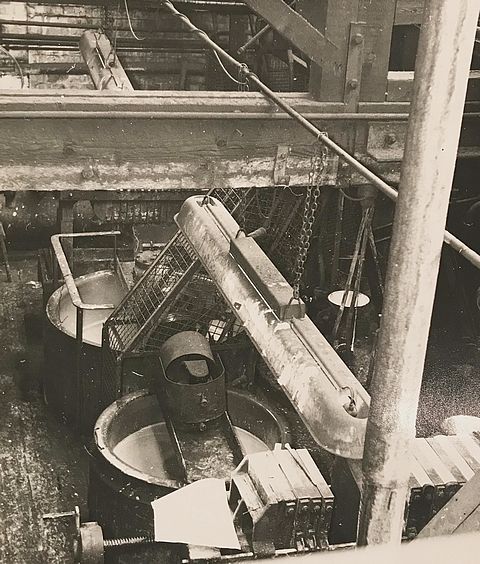

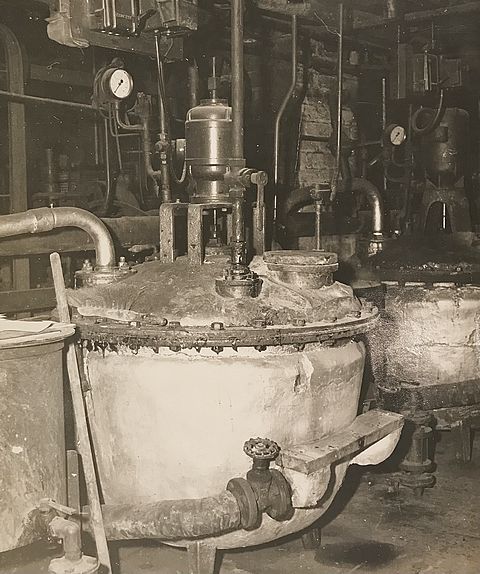

PROCESSES There were a few more complex processes such as the manufacture of glycin which I believe was a precursor to metol. These were sold as powders, but primarily they went into the solution developers. These processes were very dirty and possibly because they were photographic developers, the dust settling on the wooden floors and handrails went black quite quickly. So it was a little like working in a coal yard! I cannot now recollect the processes (and chemical reactions) for these and other products, but they involved steam heated glass-lined kettles (made by Pfaudler) and plate and frame filter presses. All mostly manual operations. |

|

|

John says: The photos were taken in the plant where glycin was manufactured and then converted to metol. You can see how black and dirty it was. There are the filter presses, with their black filter cloths and the occasional new white one, the overhead line shafts for driving pumps and mixers, some insulated kettles (it’s 100% for sure the insulation was asbestos). Not a great working environment |

|

|

|

A very profitable product was para-aminophenol, made from the nitration of phenol in a building to the north side of the site. Although originally invented as a photographic developer, it was the intermediate to the manufacture, by a pharmaceutical company elsewhere, of paracetamol, which was just becoming a popular pain-relieving alternative to aspirin and was known at Johnsons as 'para base'. They worked shifts on this as they could sell all they could make. One relatively sophisticated piece of equipment in this 'para base' plant was a scrubber used to wash some vent gas using caustic soda solution on a consumable basis. Because of the corrosive nature of the caustic, the scrubber, made by a company called Kestner, was constructed of reinforced fibreglass. Prior to its introduction, the unwashed vent gases had caused problems in the houses in nearby Park Road area, depositing a black soot in rooms through open windows. Apparently, prior to the introduction of this scrubber, several employees were sent round, on a regular basis, to clean up this mess. Although the scrubber had solved the emission problem, one afternoon, quite late, the shift foreman, George Brand, rushed into and through the lab and into the office of the Production Manager, named Dudley Wright. "Dudley, the scrubbers exploded" were his exact words. It was not an explosion caused by an over-pressure, but the glass fibre rotor in the scrubber had disintegrated and smashed the external casing. Kestner's response was that it had not been installed upright and hence the rotor was out of balance. These scrubbers were not off-the shelf items, and so to maintain output, the plant was restarted in the 'black soot' emitting mode. Another process was to produce, in a very small scale, all glass, plant, Resorcinol. I have no idea of its use, but it was of very high value and one of the initial ingredients was reindeer moss that was imported, I think, from Finland. The foreman for this unit was Frank Butcher. There was also a large area of unused plant, used in the past to make hydroquinone, which was used as a photographic developer, especially in conjunction with metol in the MQ developer. This plant consisted of many steam-heated, glass-lined open kettles (like modern cauldrons) arranged in long lines. These had elevated wooden walkways where operators stood over the kettles, stirring the liquor being crystallised, using long wooden paddles. The quinine used in the process attacked the eyes and there were a couple of men who'd worked in this facility, and were still at Johnsons, who had a condition called 'white eye', where the cornea was completely clouded over. I'm not sure of its purpose, but attached to the hydroquinone plant was a very large Heath Robinson-type vacuum pump. Fascinating to watch when it was demonstrated to me. Another plant to employ a vacuum pump was the manufacture of pyrogallic acid crystals, which I believe is the oldest photographic developer. This was made by the autoclaving of gallic acid and condensing the pyrolised vapours in a drum under a vacuum of 2 to 4 Torr (2 to 4 mm Hg). The lower the vacuum the whiter the product and the greater its market value. The vacuum pump was a two-stage pump manufactured by Pearn, a Manchester company. This was a very old and unreliable machine and at the end of the batching process, which took a day, the drum was opened and the colour of the deposited crystals indicated the success of maintaining the pump seals and hence the vacuum produced. The crystals were pure white to a light beige and the operator did his best, by hand, to separate the different coloured crystals to maximise the overall value of the batch. |

|

PEOPLE The Works Manager was Dudley Wright who had an office in the laboratory where I worked. I was seated in the open office area with my immediate 'boss' a Production Chemist called Peter Fitzgibbons. There were two other Production Chemists with their own offices in the lab: Bill Driver and ? Brewer. Many of the personnel appeaar on an organisational chart on the web page, here. The Works Foreman was Arthur Hooper, a real gentleman and a great initial support to me. Unfortunately, within a few weeks of my arrival, he was diagnosed with cancer and I never saw him again except for a single visit to the lab (primarily to see Dudley Wright) just prior to his passing and he looked very unwell. I was treated very well by Dudley and his team and regarded as one of the permanent employees, although I was in reality a paid student. Every morning, about 10 a.m., I joined Dudley, Arthur (before he left) and the Production Chemists for a tour of the works to discuss with the various Production Foreman any issues, problems, suggestions, etc. Although I can still see faces from that time, most names elude me. Some names I recollect were brothers George and Stan Brand, the former was one of the foremen in the 'para base' facility and Stan, I think, was something to do with works maintenance. Bert Gibson was the very nervous foreman in charge of making up liquids. Unfortunately, I cannot recollect the very dapper chap with a small moustache who was foreman in the glycin/metol plant. Steve Agapiou (spelling?) was the Greek Cypriot operator in the pyrogallic acid unit, which he ran and maintained vacuum with an almost religious zealotry. A Scot called Jake ran the Magnol Resist facility. John Butcher ran the small accounts office, adjoining our lab. He, most evenings, gave me a lift to Harrow-on-the-Hill station. Working with him was a comptometer operator Margaret, who moved away during my work period to East Anglia - something to do with Ted, her husband's job. Also, a young Irishman called Finton, who I lunched with most days. In the new laboratory, on the opposite side of this lower part of the site, I became friendly with a South African chemist, Mike Karwan, who left during my period to start work in an estate agent owned by a relative. He worked with a very sophisticated young lady chemist called Paula. Harry was an odd-job man around the site, who made periodic visits to our lab to tidy up things. He was probably past normal retirement age and had this 'white eye' condition I mentioned previously, a result of working over the open crystallising vats in the hydroquinone plant. Another person on the organisational chart is Dr Barrett, who was at one time a senior chemist within the organisation. At my time he was retired, but apparently as a favour (by someone high up in the Company) had been permitted to come back and use part of the laboratory in our building to develop a wet process for photocopying. The Xerox process was not generally available at this time, and this was a proposed alternative. Looking back, it was some sort of photo process and I recollect the sheets came out of the copier damp and somewhat curled up. It never came to anything, I imagine. Finally, I mention the Personnel Manager but his name escapes me. Johnson's had a very peculiar system for recording late work arrival for staff. There was no formal clocking in and out for staff, but if you arrived late then you were supposed to go to the Main Office and sign a book. The Personnel Manager often concealed himself behind bushes on the lawned area by the Canteen; firstly, to record late arrivals and secondly, to check who of the late comers signed in. All very sneaky, but he endeared himself to Management. |

|

HEALTH AND SAFETY Some operations involved separation of crystals from their mother liquor using centrifuges; the centrifuge retained the crystals which were removed manually. These centrifuges were made by Thomas Broadbent, a Huddersfield company, and were called pendulum centrifuges. They were supported at 3 points on vertical steel rods fixed to the floor. Inserted in these rods were steel keys which the centrifuge sat on and in this way the centrifuge could move sideways in all directions to accommodate any imbalance in its loading. One or more of these keys frequently broke, an issue not helped because once this had happened, the original factory-fitted high tensile keys were replaced with ordinary mild steel keys, cut and filed up in the fitter's workshop. Because the centrifuge at speed functioned as a gyroscope, when the key broke one side dropped, and the centrifuge behave erratically. This occurred on two occasions in the 6 months I was at Johnsons and each event was accompanied by a lot of noise and shaking and damage to the centrifuge. Apparently, on one occasion, prior to me working there, the dropped centrifuge had torn itself free of its mountings and set off on its side, like a giant steel wheel, and had torn through three brick walls before finally coming to rest. Freddy Kreslins was a very chatty and friendly Polish chap who worked on small batches of special chemicals which used one of these centrifuges. One of these chemicals was potassium dichromate, which I believe had some obscure photographic use. Although a basic face mask was worn when emptying the centrifuge using a small trowel, these masks very quickly turned yellow from the fumes given off. This implied the fumes were breathed in and they were very aggressive. Another problem equipment was the steam jacketed glass lined kettles used primarily for crystallisation. The jacket often corroded through, leadin to the vessel being condemned and sent to the tip at the far west end of the site. Allegedly, a previously condemned kettle would then be taken from the tip, re-installed and put back in use pending a future visit of the Factory Inspector. There was a fire in a tubular heater used to heat the autoclave in the pyrogallic acid plant. This was a furnace with oil-filled tubes which in turn were heated by fuel oil. One of the tubes burst and the escaping oil caught fire. It took some time to put out the fire and during this time a large quantity of very dense black smoke was produced together with a lot of soot. One of the processes used Ferric Chloride and I believe this at one time had been made on site, but at my time was delivered by bulk road tanker. Somehow this yellowy-green liquid had escaped as a fine spray and got on the paintwork of cars belonging to two of our Chemists. There was considerable discussion and acrimony as to who was culpable, arguments that were still on-going when I left. A final story: many of the

photo-chemicals being tested got on one's hand even if wearing

rubber gloves. Over a period of a week these would darken and

each Friday afternoon I washed my hands in the following fashion: |

|

SUMMARY The one thing that does strike me now, and it is my own perception, is that large parts of the Hendon Way site was off-limits to me. Primarily these were the larger labs and offices, though I had free reign to wander in the Works. In this context I feel that there was generally a big divide between the Works and the other persons on the site. I saw little evidence of these factions mixing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||