| Kodak Black & White Printing Paper, Films and Chemistry - by Michael Talbert |

| The images immediately below have been sent by Emmett Francois in Vermont, USA. They are scans from the January 1905 edition (Vol.VIII, No.1) of 'Camera & Darkroom Magazine', published monthly by The American Photographic Publishing Co; 361 Broadway, New York. The first image, left below, is the cover. The other three images are Eastman Kodak adverts which appeared in this edition. | |||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

|

|

|

In the early 1970s Michael Talbert had worked as a black and white/colour printer/general studio assistant for a photographer who had used Kodak bromide papers since around the time of the 1946 paper codes changeover. He had a bookcase full of old Kodak paper boxes in which he stored his negatives, some of which had both codes printed on the labels. That’s what got him interested in the old codes for paper, and he decided to find out more. Kodak VELOX paper was a very slow printing paper, producing a blue-black image, suitable for contact printing only, where the negative is placed in contact with the paper to produce a print of the same size. Kodak discontinued the manufacture of Velox paper in 1968. By way of example of its coding names, before & after 1946: Velox WVL 3 S = White Velvet Lustre, Hard, Single weight. Pre 1946: V V 3 = Velox Velvet Vigorous, single weight. Kodak BROMIDE, BROMESKO

and ROYAL BROMESKO papers

were fast enlarging papers, suitable for use with any type of

black and white enlarger. They could also be used for contact

printing. Bromesko produced a warm-black image. Its first

mention is in the British Journal Of Photography Almanac for

1938, within the Kodak Adverts. About 1940 it was available in

6 surfaces, and by 1946, when Kodak changed their coding

system (see below), it was available in Glossy, Velvet, Matt,

Rough Lustre, and Fine Lustre. Later there was a Cream base,

coded CFL 3D; a brownish red colour base, like a sepia toned

print. The paper was also made on White and Ivory (a yellowish

white) bases. Kodesko is another paper Michael Talbert has found reference to. It was a warm toned paper manufactured by Kodak in the 1930s, before Bromesko. It was unusual in that it had a parchment-like quality and was semi-translucent. The 1933 Kodak Professional Catalogue states that prints could be mounted onto a light coloured backing paper. When the print was held over a light, it “glowed”, taking on the tones of the backing paper. Maybe that is where the name Bromesko originated. Royal Bromesko paper was introduced in 1962 and discontinued in the late 1970s. It was an enlarging paper giving a warmer image tone by direct development in Kodak D-163 developer than Bromesko paper processed in the same developer. For maximum warmth, Kodak “Royal Bromesko” developer produced an almost brown and white image on Royal Bromesko paper. It had a slightly lower printing speed than Kodak Bromide or Bromesko papers. It could be handled under a Wratten Safelight filter Series OB. VELOX, BROMIDE and BROMESKO; Naming & Grading Pre-1946 Prior to 1946, Kodak’s grading system and paper

nomenclature were a complete muddle ! By way of example of coding

names, before & after 1946: Bromesko CFL 2 D = Cream Fine

Lustre, Normal, Double weight. Pre-1946: 47 Z = Cream Lustre,

Medium, Double weight. NIKKO is an early trade name for Kodak Glossy Bromide paper (in the UK). It is uncertain when the name Nikko dates from, but it is listed under Bromide papers in a Kodak 1923 catalogue. It is believed the name is pre-WW1, if not earlier. For example; Nikko BG2 = Bromide Glossy Grade 2 (medium) single weight. Contrast Grades for Kodak

Bromide papers, early 1940s

(as far as Michael Talbert can establish) were: Contrast Grades after 1946. Kodak changed their coding system relating to paper grades, types of paper surfaces, for Bromide, Bromesko, and Velox papers in 1946. Nikko BG2 then became Bromide WSG 2S = White, Smooth ,Glossy, 2 (Normal Grade), Singleweight. The new coding system for Bromide, Bromesko and Velox papers stated Tint, Texture, Surface, Contrast Grade No. and Weight, in that order. Extra Soft = Grade 0; Only

made in Velox Paper at this time. In 1948-9 paper packing quantities were standardized

to 10s, 25s, 50s and 100s (rather than by weight or in dozens

or half-dozens of sheets) and Kodak changed their system so that

all surfaces and grades matched for Bromesko, Bromide and Velox

papers. The coding system

was e.g. Bromide, White Velvet Lustre, Normal Double Weight =

Bromide WVL 2D. The pre-1946 code was BV 2Z, Bromide Velvet Medium

Double Weight (the letter Z was used to indicate Double Weight). Kodak Papers, 1949 |

|

|

|||

|

Bromide Paper; 1905-1910 Quoting from the Introduction to Brian Coe's excellent book 'Kodak Cameras - The First Hundred Years': "The Kodak presence in Britain had developed from the wholesale importing agency set up in 1885 (under William H.Walker). (This led to) .....the formation of the Eastman Photographic Materials Company in 1889, set up to manufacture and market (George) Eastman's products, (and) taking over the business and markets of the Company outside north and south America. At the factory at Harrow, then outside London, photographic film and paper were manufactured, and the developing and printing of customers' films was carried out". The Kodak Limited was formed in November 1898 and acquired the business of Eastman Photographic Materials Company, Limited. Interestingly, Kodak Limited still exists (May 2020). Gavin Ritchie tells me it is company number 59535, incorporated on 15th November 1898. Its original registered office was 43 Clerkenwell Road, London EC but by 6th June 1972 the registered office was Kodak House, Station Road, Hemel Hempstead, Herts. The present day registered office is Building 8, Croxley Green Business Park, Hatters Lane, Watford, Herts, WD18 8PX. Michael Talbert has an 8-page leaflet dating from the early 20th century (he estimates 1905-1910), not long after Kodak Limited had acquired the business of the Eastman Photographic Material Company. The first two pages of that leaflet are shown to the right. It contains information about Eastman's Bromide, Royal Bromide and Nikko papers, by then being sold under the Kodak, Limited name. it proclaims: |

|

||

| To the right is a bromide paper price list, taken from the same leaflet. |

|

||

|

|

|||

| Kodak Platino Matt Rapid Smooth Bromide; pre-1911 | |||

|

An image of a Bromide paper packet sent to the author from Auckland Memorial War Museum, New Zealand. Kodak Platino Matt Bromide Paper. Auckland War Memorial Museum Tamati Paenga Hira. EPH-ARTS-2-3. The image has the Kodak address of 'Clerkenwell Road, London EC'. This was the address of Kodak Limited before the company moved to Kingsway (between Aldwych and High Holborn, London). It seems the building Kodak inhabited at No.63 Kingsway, London was built in 1911. Ref: The Construction Index from May 2021 reads “It was built in 1911 to house offices, store rooms, darkrooms, printing rooms, a shop and warehouse”. It was refurbished by Gilbert–Ash in 2021–22 and is known as “The Kodak” with an entrance from Keeley Street. Platino Matt Rapid Smooth paper is included in the 1905 – 10 price list (see above) at 3 shillings and three old pence (3s.3d = about 16p). It is not clear if the paper weight is single or double, or if it is the same paper as 'Platino Bromide' paper mentioned in the 1905-10 leaflet (above, right). It is listed in the 1922 catalogue (see below, left) as Platino-Matte, Rapid Smooth. Due to it showing the Clerkenwell address, it is probably safe to assume that this packet dates pre-1911. The date 4.21 on the packet which follows (see below) may mean it dates from April 1921 as this has the Kingsway address on it. Perhaps Kodak started printing the code dates on the labels when they were at Kingsway. |

|||

|

|||

| Nikko Paper; c1921 | |||

|

The image below of a packet of a Kodak Nikko Bromide paper packet came from the 'Canterbury Museum' Canterbury, New Zealand. Michael Talbert saw the image amongst other pictures of Bromide packets and the museum agreed it could be reproduced on Photomemorabilia but required it to be acknowledged by way of the reference "Kodak Nikko Bromide Paper, Eastman Kodak Company. Canterbury Museum. Ref: PH/78.19. NZ. The packet may date from 1921 by virtue of it having B.P.134.10m 4.21 on the label. The numerals 1/3 written on the packet presumably refers to its price when new, being 1s/3d = 15 old UK pence; 6.25 new pence). This is 1.875d (old UK pence) per sheet. The 1905-10 price list (above, right) shows the same size Nikko paper (6½ x 4¾ inch=½ plate) but offers a dozen, i.e. 12 sheets, for 1s/6d (18 old UK pence). This is the equivalent of 1.5d (old UK pence) per sheet, hence cheaper than the 1s/3d pcket price. The 1922 price list, below right, shows 7 sheets being sold for 1s (no differentiation between Nikko and standard bromide), which is the equivalent of 1.714d (old UK pence) per sheet; still cheaper than the packet price, but much closer. Since Nikko is listed as being more expensive in the 1905-10 price list than standard bromide (maybe dependent on the amount of silver bromide used when coating the paper), its possible the 1922 price list of bromide papers under-estimates the price for Nikko paper. Also, since there is no indication of the weight of paper that was in the Nikko packet, there is little point in trying for too fine a comparison. The best that can be concluded is that the packet shown here most likely dates from the early 1920s and the (already suggested) 1921 date may be correct. The 1922 price list (on page 60; see below, left) describes Nikko paper as being "a glossy bromide with a highly enamelled surface. Gives very soft effects. Made in Mauve-White and Pink". The 'Enamel' surface type and 'Mauve-White' colouration, both fit the packet illustrated. The bracketed term (Rapid) after the Nikko name in the 1922 information, suggests a higher silver bromide content. |

|||

|

|||

| Information and Prices of Bromide Papers in 1922 (Ref: Photographic Catalogue; W.Middleton Ashman & Co; 12a Old Bond Street, Bath; pages 60 and 61) |

|||

|

|

||

| Nikko Soft Grade Paper; c1930 | |||

|

A box of Kodak single weight 'Nikko' Bromide paper in 'Soft' contrast grade. In the early 1920s the Kodak Professional catalogues described Nikko Bromide paper as “A glossy surface paper for rendering of fine detail. Specially suitable for Press work.” At this time, Nikko paper was made in one contrast grade only and the paper had a slightly mauve tint to the base. A separate Bromide paper with the name of 'Contrast' was obtainable in glossy, velvet, matt, and 'Permanent Smooth', being a semi-matt surface. Contrast paper was suitable for soft, under exposed negatives. By 1930, three contrast grades of Nikko were available in Soft, Medium and Contrast. The Contrast paper mentioned above was then included within these grades. It is thought that this box

of Nikko paper dates from when Kodak UK bromide papers were first

available in three grades and the introduction of sealing labels

showing a code for the type of paper surface together with a

grade number. Nikko had always been known as a glossy paper and

in the late 1930s this paper would have been known as 'Nikko

Soft BG-1'. Kodak bromide paper may have been produced in three

contrast grades from the late 1920s (perhaps 1929), and sealing

labels for papers printed with descriptions and grade numbers

may have originated around 1934.  References: Kodak Professional Photographic Apparatus

and Materials, catalogues 1923 and 1933. |

||

| Bromide Paper Code Table, 1939 (and 1935) | |||

|

Below is shown a table of Kodak UK Bromide Papers which could be purchased from Kodak in 1939. The table gives all the surfaces, paper contrast grades and codes with the grade numbers in single and double weight paper. This table is rare because the Kodak UK catalogues give no indication of any codes in the Bromide paper availability lists of the surfaces and contrast grades. The table equally applies to the Kodak Bromide paper availability in 1935, but in 1935 there were no Grade 5 (extra Contrast) papers obtainable apart from 'Nikko' BG-5 and BG-5Z. (Reference: Westminster Annual of Photographic Accessories 1939.) |

|||

Contrast Grades: |

|||

| Kodak Bromide Papers BV-4 and BRW-4 Z; c1937 | |||

|

|

||

| Kodak Bromide Papers BRTF-1 Z, BRIWF-2 Z, BG-2, BV-2, BBS-2; c1938 to c1946 | |||

| Although these sealing labels are stuck onto 1940s design packets, they may be identical to late 1930s sealing labels. | |||

|

Kodak Bromide enlarging paper BRTF-1 Z A bromide paper label dating from the 1940s. Bromide Royal Tinted Fine (grain) – Soft (1) Double Weight (Z). The base of the paper was a yellowish brown, and gave the impression of a sepia toned print. 'Tinted' and 'Cream' had almost the same coloured base, although the 'Cream' was slightly more red. The 'Tinted' base was only suitable for certain subjects, such as photographs taken under interior room lighting, sunsets, portraiture. Cream base paper began to look old fashioned by the late-1960s and Kodak withdrew their cream base papers about 1967. |

||

|

Kodak Bromide enlarging paper BRIWF–2 Z A bromide paper dating from the 1940s. Bromide Royal Ivory White Fine (grain) – Medium (2) Double Weight (Z). This paper was available in

double weight only, in sheet sizes up to 20 x 24 inches,

and in bulk postcards. Manufacture ceased after 1946, but the 'Snow White Fine (grain)' and the 'Tinted Fine (grain)' tints and surfaces were obtainable in certain sheet sizes for a few years after 1946. 'Ivory White' was described as a paper “…………..between a cream and a white, and imparts just that warmth of tone to the average enlargement that is sometimes lacking in papers with a mauve-white base”. The Kodak glossy bromide paper

manufactured pre-1946, known as 'Nikko' paper, had a mauve-white

base. |

||

|

Three labels from packets of Kodak Bromide paper dating from the late 1940s. The top label, BG-2, is Bromide Glossy (2), Medium contrast, single weight, known after 1946 as WSG 2S. (White Smooth Glossy, Normal, single weight).

The middle label, BV-2, is Bromide Velvet (2), Medium contrast, single weight, known after 1946 as WVL 2S. (White Velvet Lustre, Normal, single weight). This label has been altered from a label denoting “Double weight” paper, as the “Z” and “Double weight” has been crossed out. This is typical of paper manufactured during the “change over” period of labeling and quantities.

The bottom label, BBS-2, is Bromide Black Smooth, (2), Medium contrast, single weight, known after 1946 as WSM 2S, (White Smooth Matt, Normal, single weight). Below (scroll down six images) is a photograph of a later label, post 1946, of this surface in Soft grade, WSM 1S.

As best can be determined, Kodak “Crayon Black” Bromide paper was introduced in 1940 in Smooth, Natural, and Rough surfaces. The British Journal of Photography Almanac for 1941 describes the smooth surface as “An excellent material for medium sized prints which are to be handled a good deal”. Pre-1940, the paper was known as “Platino Matt Smooth”. In 1946, the name of the paper was changed to “White Smooth Matt” and was available on a single or double weight base in three contrast grades. Bromide White Smooth Matt and Bromide White Velvet Lustre were replaced by a new surface, “White Semi-Matt”, (WSemiM), in 1971. |

||

| Kodak 'Nikko' Bromide Paper, Extra Contrast, BG-5; c1940 | |||

|

'Nikko' Bromide glossy paper, in single and double weights, became available in the 'Extra Contrast' grade shown left, here, in 1934. Extra Contrast was suitable for making prints from very soft, or under exposed negatives. Initially, the grade was available in 'Nikko' paper only, but by 1938 it had been extended to four other double weight Bromide papers (see Kodak Bromide Code Table, above). In 1946 the paper was renamed Bromide 'White Smooth Glossy, Extra Hard', (Grade 4) in single and double weights, with the codes WSG-4S or WSG-4D. This packet may date from 1940, the rear sealing label gives a number – 'P2 15540', possibly referring to May 1940. All types of Bromide paper were replaced by 'Kodabrome II RC' paper, a resin coated paper, in 1982. References: |

||

|

|||

| Sealing Labels From Packaging Showing Code Changes; 1946 - 1950 | |||

|

For a time after 1946, most Kodak Bromide and Bromesko papers carried labels with both the new codes and the old codes relating to the various surfaces. These pictures (left and below) show three such labels. The Bromide box shown to the left has the new code WSM 1.S – White Smooth Matt, 1 (grade) S (Single Weight). But its label also shows that, pre-1946, it was known as - Bromide Crayon Black, Soft, Single Weight. The old code gives it as BBS 1 - Bromide Black Smooth 1 (grade). The 'Smooth' is added to differentiate this particular surface between 'Crayon Black Natural' and 'Crayon Black Rough', two surfaces of Bromide paper sold pre-1946. Bromide papers made prior to 1946 were never made in Grade 3 Vigorous. Hence, e.g. when the new codes for Bromide paper were introduced in 1946, 'Nikko' Bromide paper BG 4 Contrast (see below) became WSG 3.S (White Smooth Glossy, Hard, Single Weight). There was never a code of Bromide BG 3 or BG 3.Z |

||

|

|

||

| Bromide Instruction Sheets, 1938 to late 1940s | |||

|

The instruction sheet to the left dates from 1938. This instruction sheet comes from a Kodak Bromide paper packet 'Bromide Royal White, Grade 4, (Contrast) Double Weight' (BRW-4Z). It was printed in January 1938, by reference to the number printed at the bottom left of the sheet – P.F. 300138. The instruction sheet unfolds to reveal instructions printed in 12 languages. The Kodak D-157, which is recommended for developing Kodak bromide paper, was an early version of the Kodak Bromide paper Developer D-163, also known as Kodak 'Special' Developer. The sheet shows the Kodak formulae

for Developers D-157 and D-162. |

||

|

It shows the Kodak formula for Kodak D-163 Developer, which has slight chemical changes compared to the previous D-157 developer. It also give the Kodak formula for D-170. The sheet is printed in four languages.  |

|||

|

Below is shown a 3rd Bromide

paper instruction sheet. It has been divided into two halves

(below left and right) for convenience of display. The uncertainty about the printing

date of this sheet arises from the last paragraph, which reads:

Glazing. 'Nikko' (glossy) bromide paper ........etc. Hence the difficulty in dating this instruction sheet accurately. |

|||

|

|

||

| Kodak Bromide Paper WSL 1.S; 1947-1949 | |||

|

This box design, with its red and black parallel lines, dates from 1946. The two pictures (left) show a box of WSL 1.S paper, White Smooth Lustre, Soft Grade, Single Weight, made by Kodak Ltd; UK. It was available in this form from 1947 to 1949. The surface may have been identical to a Bromide paper known as “Permanent Smooth” single weight, manufactured with this name at least since the 1930s. In the UK Kodak Professional Catalogue for 1923 the paper was listed as “Permanent”, obtainable in “Rapid and Slow Smooth” and “Rapid Rough” surfaces and speeds. By 1930, the paper was known as “Permanent Smooth”, described as a “rapid natural surface paper with a slight sheen, made in single weight only”. At some time between 1943 and 1946 the paper was marketed as “Bromide Velvet Smooth”, as shown on the packet's rear label (see left; lower of the two) as “Previously known as:- Bromide Velvet Smooth, Soft BVS 1" The name of the paper changed again in 1946 to “White Smooth Lustre” obtainable in single weight only. The paper was also marketed from 1946 as "Bromide Royal White Smooth Lustre” (WSL) in double weight only plus two more paper base tints, Ivory (ISL) and Cream (CSL), and there was an “Air Mail” version, “Bromide White Smooth Lustre, Light Weight”, made with an extra thin base to save on weight and the photographs could be folded without damage. By 1949, the single weight version was no longer manufactured. In 1951, the paper became known as “Bromide White Smooth Lustre”, the “Bromide Royal” series of papers and the Ivory and Cream base tints having been withdrawn. “Bromide White Smooth Lustre” in double weight remained on the market until 1970 when replaced by “Bromide White Semi Matt” (WSemiM), a paper with an almost matt surface with a very slight sheen. Velox paper was obtainable in “White Smooth Lustre” surface from 1959 to 1961, and Bromesko paper, “Ivory Smooth Lustre” (ISL) was manufactured in mainly continental sizes from 1958 to 1961. In 1962, the new “Royal Bromesko” paper was obtainable in “Smooth Lustre” surface in White and Ivory base tints (WSL and ISL). |

||

|

|||

| Packaging Change From Brown/Grey to Yellow, WSG 2.S and IFL 2.D; c1953 | |||

|

The Bromide WSG 2.S box (the left most of the two shown alongside; the upper of the two in the enlarged section) is of a design that dates from 1946. The box shown must be an early box of this design as the sealing label (underneath the box) still has the 'change over' code printed on it – 'Nikko' Medium – BG-2. It is believed that 1953 was the year that Kodak, London, introduced the yellow packaging for their black and white printing papers. Thus, the Bromide IFL 2.D box (the right most of the two shown alongside; the lower of the two in the enlarged section) dates from approximately 1953 to 1958. The red and black vertical line design was changed in 1959 to two offset rectangles that read 'Kodak' and 'Photographic Paper' (see the box of Bromide WSG 1.S below). |

||

| Bromide Instruction Sheet 1952 | |||

|

The instruction sheet shown below (front and back) is for Kodak Bromide paper, dated October 1952 – Ref. No. on bottom left on page 2; PF1052 RL201. Since 1950, a new safelight filter, Wratten Series OB, a lime-yellow colour, had been in use replacing the Wratten Series OA filter, coloured olive. The Wratten Series OB filter was suitable for Bromide and Bromesko papers. Kodak was now recommending 68°F (20°C) as the correct temperature for developing Bromide and Bromesko papers in their paper developers such as D-163. The formula for D-170 was still being printed in the instruction sheet, but gradually Kodak 'Universal' liquid developer was replacing D-170. |

|||

|

|

||

| Whiter White Paper Base, Advert; 1953 | |||

|

but also to Bromesko and Velox papers. |

||

| Packaging Change; Two Offset Rectangles; From c1959 | |||

|

The red and black vertical line design on the boxes shown in the images of the WSG 2.S and IFL 2.D boxes, above, changed in the UK in the late 1950s to one where 'Kodak Photographic Paper' was printed in two rectangles, see alongside and below. A very similar design was used by Eastman Kodak in the USA, from the late 1940s. In the 1950s and 1960s, Kodak Bromide paper was generally made with a white base. The 'Fine Lustre' surface was the only surface in the Bromide range made with an Ivory tinted base. By 1969, the Ivory tinted paper was no longer sold in the Bromide range of papers, although Kodak continued to make Bromesko Ivory Fine Lustre paper until the mid-1970s. The rear labels of these two boxes can be seen below; WSG.1S (left; mid-1950s to early 1960s) and WSG.3S (right; early 1960s).  |

||

|

|

||

| Packaging Change; Horizontal Red and Black Bar; From mid-1960s | |||

|

The box and packet design dating from the mid-1960s to the mid 1970s.  |

||

|

|

||

| Bromide Instruction Sheet 1967 | |||

| Below is shown a Bromide paper instruction sheet dated 1967 (inferred from PF 4-67 at the left hand bottom of the page). The original sheet has been scanned in two halves (below left and right) for convenience of display. | |||

|

|

||

| Packaging Change; Large Red Rectangle; From mid-1970s to 1982 | |||

| The right hand

box (WFL.3S in the pictures below) was the design from the mid-1970s. Then, the 'Notice' (conditions of sale information) was omitted from the box front design about the end of the 1970s. See the WSG.3D box below left and further below left for the 'Notice' text. In the final design to 1982, the word 'Photographic' was omitted in the box front description 'Kodak Photographic Paper'; see last box image, right. Boxes and packets bearing the last two designs were used concurrently. |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Soft Grade 1, Extra Soft Grade 0 and Grade 1

Special Contrast Bromide Papers In the 1930s, an Extra Soft, or 'Grade 0', was available in Kodak Velox paper in two surfaces, Glossy and Art = semi-matt, in single and double weight paper. In 1946, Glossy became White Smooth Glossy, and Art became White Velvet Lustre, in single weight only, coded WSG 0S and WVL 0S. In 1940, Kodak Press Bromide paper was listed in the Kodak catalogue as having five grades of contrast = Soft, Normal, Medium, Contrast and Extra Contrast. Press Bromide paper was designed for processing and printing under 'rush' conditions, and was described as having 'exceptional latitude'. From 1946, when Kodak in the UK changed their paper grading system, Press Bromide paper continued to be made in five contrast grades, but now the previous Soft Grade became Extra Soft = Grade 0, Normal became Soft = Grade 1 and Medium became Normal = Grade 2. This was a more logical contrast range description, running from 0 = Extra Soft to 4 = Extra Hard in a glossy surface only, coded WSG 0S to WSG 4S, meaning White Smooth Glossy, contrast grade number, Single Weight. By the mid 1950s, the regular Kodak Bromide paper was being sold in the same five contrast grade range in the glossy surface only. The Grade 1 = Soft grade was manufactured in most surfaces and weights of Kodak Bromide, Bromesko, Royal Bromesko, and Velox papers, but Grade 0 = Extra Soft was confined to Bromide Glossy, mainly in single weight, and then only made available in certain sizes and quantities. Manufacture of Kodak Bromide paper in all grades ceased in 1982; to be replaced by Veribrom and Kodabrome II papers. The Extra Soft grade was obtainable in five paper sizes, single and double weights, up until the 1982 withdrawal of Bromide paper. |

|||

|

|

||

| Below is shown front and back of an advertising leaflet for a new grade of extra soft contrast Bromide paper, Grade 0. The leaflet is believed to date to March 1956. | |||

|

|

||

|

Boxes of Soft Kodak Bromide paper, dating from the early 1970s WSG.0D = White Smooth Glossy, Grade 0 Extra Soft, Double

Weight. WSemi-M.1D = White Semi Matt, Grade 1 Soft, Double

Weight. WSemi-M recorded fine detail well, and prints could be retouched easily. The surface was slightly more matt than the “N” lustre surface in Kodak's range of colour printing papers. The paper was also available in single weight. |

||

|

Grade 1, Special Contrast WSG.1 S The paper was available in sizes from 6½ x 4¾ inches to 10 x 12 inches. The labels from a 100 sheet box can be seen below. Grade 1 Special never really caught on. Kodak withdrew the paper from the market in 1972 and the grade was never reinstated. The author comments: |

|||

|

|

||

|

Bromide

Air Mail Paper Bromide Foil Card

Paper Bromide Air-Mail and Foil Card were available in Soft, Normal and Hard grades, also the various Royal Bromesko and Bromesko (ISL) paper. |

|

|

|

|||

| Two Early Prints on Royal Bromide Paper ~ c1910 | |||

|

The picture below (right) came into the possession of Peter Vaughan's father when he took over running a chemist's shop during the 1960s. It is now held in Peter's possession and he has given permission for it to be displayed here. He says "It is behind glass, so please excuse the reflections". It was taken using a No.4 Cartridge Kodak using a wide angle lens and "Enlarged upon Eastman's Royal Bromide paper". The No.4 Cartridge Kodak was manufactured from 1897 to 1907 (Ref: Brian Coe). It took a large roll film with a 5” x 4” format. A label on the reverse of the print (see below, left) tells us that the frame and contents are the property of Kodak, Limited, successor to the Eastman Photographic Materials Co.Ltd; "It is particularly requested that the exhibit be promptly returned to Kodak, Limited, when required by them". Seemingly, Kodak never asked for the print's return and by the 1960s it had ended up in the chemist's shop owned by Peter Vaughan's father. There is no date on the label, but by combining the manufacturing date of the camera used and Michael Talbert's information (above) it could be 1910 or a few years earlier. |

|||

|

|

||

| Another early

print on Kodak Royal Bromide paper, perhaps from a silmilar era

to the picture above, pre-WW1. This one is owned by Gavin

Ritchie and shows a scene believed to be from the Henley Regatta. Henley Royal Regatta is a rowing event held annually on the River Thames by the town of Henley-on-Thames, England. It was established on 26th March 1839. |

|||

|

|||

|

In the 1905-10 leaflet (above) it says "Royal Bromide Paper

is an antique cream tinted paper, with a surface like hand-crafted

paper, and is of such substance that, for many purposes, mounting

is unnecessary". Before 1940 the range of Bromide Royal paper consisted

of a range of four variants: After 1940 (Taken from the British Journal Photographic

Almanac, 1941). Michael Talbert comments: "What a mix up of Bromide papers! No wonder Kodak wanted to introduce a new coding system for their Bromide papers in 1946!" |

|||

| Bromide Royal Paper from 1946 | |||

|

Kodak Bromide Royal Paper BRTF-2 Z The images alongside are the front and back labels of a pack of 10 sheets of 10 x 8 inch bromide BRTF-2 Z. Kodak Bromide paper BRTF-2 Z = Bromide Royal Tinted Fine (grain), (grade) 2 (medium), Z (double weight). This paper is likely to date from 1946 until the early 1950s. After 1946, most Kodak printing papers were packed in quantities of 10, 25, 50, and 100 sheets in boxes or packets. Before this time, small sizes of paper were graded by weight and larger sizes were packed in multiples of a dozen. The paper has an extremely fine grain matt surface with a yellow base. Medium grade was for printing with normal contrast negatives. The original packaging quantity and size have been over-printed. The packet was originally intended to hold 6 sheets of 11½" x 8½" paper at the pre-1946 quantity of ½ dozen (i.e. 6) sheets. It was then changed at some point to a different size, 10 x 8 inches, with the new 10 sheet quantity specified. This particular type of Bromide paper was sold in the late 1940s in boxes and packets printed with the red and black vertical line design (see picture, below, of Bromide Royal box coded BRSWF2-Z). The sealing label and paper variety codes were never changed to the new coding system. |

||

|

|||

|

Kodak Bromide Royal Paper BRSWF-2 Z The Kodak Bromide Royal paper 100 sheet box has a sealing label which was in use prior to 1946, although the box dates from 1946 onwards. In that year Kodak London introduced a new coding system for their Bromide, Bromesko and Velox papers stating Tint, Texture, Surface, Contrast Grade No. and Weight, in that order. BRSWF 2.Z – translates as Bromide, Royal, Snow, White, Fine (grain), 2 (grade), Z (Double Weight). The other surface which was

never labeled with a new code was: In the Bromide range of printing papers at least 10 different surfaces and tints were labeled with the new codes. Another two, not included in the 10, kept their old codes and the boxes and packets were sealed with the previous pre-1946 labels – such as shown on the rear label of this box of BRSWF-2 Z. In July 1953, Harringay Photographic Supplies, surplus photo material dealers, had a half page 'spread' in “Amateur Photographer” magazine offering for sale “Kodak Royal Bromide“ papers in both the above surfaces. Four paper sheet sizes, plus rolls, were listed at vastly reduced prices. It is likely that the paper would have been out of date by 1953. See Information Tables, below 'Kodak Papers', one of a series of Kodak Photographic Handbooks, the first edition, published in 1946 and printed in January 1947, includes a list of Bromide papers that were available or becoming available at that time. Two Bromide Royal papers, BRSWF-2 Z, and BRTF-2 Z were still being sold in contrast grades of soft, normal, and hard (see Table below, left). An insert for this Handbook (see Table below, right) shows the actual photographic papers obtainable in March 1947, including Bromide Royal. The Bromesko papers became 'White Fine Lustre' and 'Cream Fine Lustre', and the Bromide 'Silk' finish papers were being made only as Bromesko paper by 1949. In the third edition of 'Kodak Papers', Handbook published in 1949, the two Bromide Royal papers, with the old surface and grade codes, were omitted. It is thought that they were no longer manufactured. References: |

||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

Kodak Bromide Royal Paper IRL 1.D IRL 1.D translates as Ivory Rough Lustre, 1 (grade = Soft), Double Weight. 'Smooth Lustre', 'Fine Lustre' and 'Rough Lustre' surfaces were manufactured from 1946 in White, Ivory and Cream base tints, on a double weight base, in three contrast grades, Soft, Normal and Hard, in the range 'Bromide Royal' paper. All other surfaces, base tints, and weights were known as 'Kodak Bromide'. As far as is known, by 1952 the use of the word 'Royal' had lapsed and the 'Rough Lustre' surface was only included in Kodak’s 'Bromesko' range of papers, as can be seen on the label (below) WRL 3.D. From 1952, all surfaces, base tints and weights of Bromide paper were labeled 'Kodak Bromide', see bottom label, WFL 1.D. Packets and boxes of 'Bromide

Royal' paper with the post-1946 coding are now extremely rare.  |

||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

The following images of a box of Kodak Libra paper were sent (Feb 2020) by Trevor White. He asked whether the authors of Photomemorabilia might know anything about Libra enlarging paper. He couldn't find any reference to it on the Internet except that Kodak are now using the name for Litho' plates. The box originally contained 100 sheets of 10"x8" grade 2 glossy doubleweight and the batch code on the side is 37741-02-15. Subsequently, Trevor heard from Erin Fisher and Todd Gustavson, both at the George Eastman Museum, who found reference to this name of paper relating to a Jesse Crittenden Ireland, trading as the 'Libra Company' of 16 Dorest Street, Salisbury (though a reference within Chemist and Druggist, for 21st May 1910, p45, gives the same address but as being in London). J.C.Ireland was applying to trademark the name "Libra" at that time, with an application number (?) of E.G. 321,403. The reason why the Libra paper should be in Kodak packaging seems uncertain, though it may have been manufactured by J.C.Ireland and Kodak marketed it. Erin Fisher also commented that the style of the box and design look to be around 1910 compared to other examples in the collection. But there remains uncertainty whether the 1910 J.C.Ireland Libra paper is the same as the Kodak Libra paper shown below. Michael Talbert commented:

Overall, this author was inclined to a conclusion that the Kodak Libra box (below) dates from the mid to late 1930s, the same age as the Bromide BRW-4 Z packet (above) with just “Kodak” printed in black. This was apparently confirmed by a discovered price list, see below the box pictures, dating to March 1936. Why Libra paper doesn't appear in any Kodak catalogues remains a mystery. |

|||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

||

| Below is shown a price list for Kodak Libra paper, dating from March 1936. | |||

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

||

| Stuart Allan recently (August 2024) noticed the above entries for Libra paper on this website, while he was looking for information on a Libra paper box in his possession. He says "I have a box (that once held) postcard paper which is different to the box design you have for the 10 x 8 inch paper" (see above). "I think the box I have could be earlier in date". | |||

|

At the bottom left of the label

it reads B.P.244.2.10.27. I have a box of 10 x 12 inch Kodak UK Bromide paper labelled 'Nikko Soft' but with no code on the sealing label. A later box would have had a label reading Nikko BG-1 i.e. Bromide Glossy grade 1; NIkko was an early Kodak UK trade name for Glossy Bromide paper. Its likely that the Libra box to the left dates from the same time, as there is no sealing label code, just Vigorous stamped onto the top of the box. Compare this to the Libra box shown above, believed to date mid to late 1930s, which has the code LG-2 Z. In the 1923 Kodak catalogue there are no contrast grades stated for Bromide papers, though there is a bromide paper listed separately as 'Contrast Bromide'. No paper is listed as 'Soft' grade. In the Kodak book 'How to Make Good Pictures', published c1927, Nikko paper appears, but again with no contrast grade. 'Contrast Bromide' is again listed, separately. In the British Journal of Photography Almanac (BJPA) for 1931, Kodak Bromide paper is (by then) advertised in Soft, Medium and Contrast grades. So the Libra box (and Michael's box of 'Nikko Soft') may date from a rime when different contrast grades were first being made and labels wre starting to show a grade and surface. Its likely sealing labels would have shown codes for paper contrast and surface by 1935. Putting all the above together, the likely date range is late 1920s to 1934. So, the label's code B.P.244.2.10.27 posssibly does refer to October 1927. |

|||

|

|||

|

Below is shown a Kodak Libra box that looks of similar age to the Libra 8 x 10 inch box shown above (first Libra entry). It has the same surface but a different contrast grade. It contained 250 sheets of Postcard size (3½ x 5½ inch) double weight paper. The paper had a gloss surface and its grade was 'Contrast', Grade 4. The paper code, LG-4 Z = Libra Gloss, Grade 4 (Contrast), Z = Double Weight. The box may date between 934 to the late 1930s. The number 1d 15934 can be found printed at the bottom left of the sealing label fixed to the side of the box (as shown enlarged below). This may denote September 1934 (last three figures). The March 1936 price list (see above) for Libra paper gives no price for 250 Post Cards, so it may be assumed that the quantity of 250 was either made to special order or that the 250 sheet quantity was not available at the time the price list was printed. It is interesting to note that by March 1936 (and perhaps by 1927 - see box belonging to Stuart Allan, above) Libra paper was available in four grades of contrast and in three surfaces, whereas Kodak Bromide papers were obtainable in only three grades of contrast, apart from Nikko Glossy. There must have been perceived a noticeable 'gap' in the available contrast grades between 'Medium' and 'Contrast', leading to the production of a 'Vigorous' Grade 3. Velox 'contact' paper grades were more evenly spaced from 'Extra Soft' to 'Extra Contrast', but it should be remembered that in the 1930s many professional photographers were exposing onto glass plates of 6½ x 8½ inches or even 8 x 10 inches. Subsequent prints would have been (mostly) made by contact printing their glass plate negatives directly (by contact) onto Velox paper, which was obtainable in several surfaces and six contrast grades and in very large sizes of paper. |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

The date that Bromesko enlarging paper was introduced into the UK is uncertain, but it was definitely available by May 1937. The left hand table below, dated 1937, shows the surfaces and contrast grades when Bromesko paper was first introduced. Originally, 'Soft' and 'Medium' contrast grades only were available, but in 1938 a 'Contrast' grade was added to the range in all surfaces and weights. (Ref: Kodak General Catalogue, 1937). The right hand table shows the surfaces and contrast grades available in 1947. The 'Cream Smooth Matt' and 'Cream Velvet Lustre' surfaces were withdrawn by about 1951 and (at that time) all the 'Double Weight only' surfaces were obtainable on a white base, not just ivory or cream. (Ref: 'Kodak Papers' booklet January 1947). Bromesko Trial Packets

of Paper No. 1 packet contained four

sheets of surface 46 Z (White Lustre), four sheets of surface

47 Z (Cream Lustre) and four sheets of surface 48Z (Ivory White

Lustre), all in Medium contrast Grade. The size of the paper in all packets was Whole Plate i.e. 6½ x 8½ inches. The paper was Double Weight (Z), and the price of each packet in 1939 was 3/- (Three shillings= 15p in decimal currency). (Reference: The Westminster Annual of Photographic Accessories 1939). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kodak Bromesko 67 Z At the time of its introduction, Bromesko paper was sold only in Soft and Medium Grades, but by 1938 a 'Contrast' Grade also became available. Thie label alongside dates from the mid-1940s and shows the code for 'Bromesko Cream Lustre' (tint and surface) in the 'Contrast' grade and Double Weight (Z) paper. In 1946, 'Cream Lustre' became 'Cream Fine Lustre' and 'Contrast' became Grade 3 Hard. The new coding after 1946 was CFL 3.D (D = double weight paper); for similaar, see below. |

|

Kodak Bromesko CFL 1.D This is a packet of Bromesko enlarging paper of similar "Cream Fine Lustre" as above, but with a post-1946 label. The label shows the new code

for Grade 1 (Soft). The pre-1946 code for 'Medium'

Grade was Bromesko 47Z. |

|

Packet of Bromesko paper made in Germany Found on the German ebay site, it's difficult to be specific about its date of manufacture because of the coding system used. It was made in Berlin, SW 68 and has the UK pre-1946 code for its surface and grade i.e 47Z = Cream Lustre, Medium (contrast), Double Weight. In German, it is labelled Creme Seidenglanz = Cream Silk Gloss, possibly because there was no equivalent Agfa black and white paper with the same surface. It’s also odd that the (contrast) grade is termed “Normal” rather than “Medium”. The packet may be about 75 years old (in 2023) but the author isn't sure, especially as Kodak in Germany may have been using the older coding system for their Bromesko paper after 1946. The UK Kodak equivalent surface and grade post-1946 was “Cream Fine Lustre, Normal, Double Weight”, or CFL.2D.  |

|

Bromesko Packaging, 1946 It is thought that these two whole plate size packets date from 1946. Both packets have two vertical lines and an outline of 'Kodak' in black. This was the original design for boxes and packets in the new range of UK made photographic papers introduced in 1946. Their rear sealing labels can be seen below the front images. Both rear labels show the names

and codes for the previous range of Bromesko papers. The yellow label was to denote Grade 3 (Hard) paper on the WSG 3.S packet. The colour of all Grade 3 labels was changed to purple in the early 1950s. Kodak were quick to colour one line in red, and 'fill in' the word 'Kodak' in red, certainly by 1947, see the pack of Bromesko IFL 3.D, further below left. Eastman Kodak, at Rochester USA, had started printing this 'red' design onto their boxes of photographic paper before the end of World War II The 'red and black' photographic paper packaging design lasted until the late 1950s. |

|

This sealing label, for a packet of CFL 1.D paper, is contemporary to the CFL 2.D packet and its rear label that can be seem to the left. The previous Bromesko 27Z Cream Lustre Soft DW had now become CFL 1.D  |

|

Bromesko IFL 3.D and Bromide IFL 2.D

These brown/grey boxes were gradually replaced by yellow boxes (lower image, alongside) during the 1950s. The red and black vertical line design dates from 1946, although the same design was already being printed onto American Eastman Kodak black and white photographic paper boxes prior to 1946. This vertical line design lasted until the end of the 1950s. The wording was changed underneath "Open in Photographic Darkroom” on the later packaging, dating from the late 1950s. The Bromide IFL 2.D box dates from approximately 1953 to 1958. It is believed that 1953 was the year that Kodak, London, introduced the yellow packaging for their black and white printing papers. The red and black vertical line design was changed to two offset rectangles that read 'Kodak' and 'Photographic Paper', in 1959 (see below). In the 1950s and 1960s, Kodak Bromide paper was generally made with a white base. The “Fine Lustre” surface was the only surface in the Bromide range made with an Ivory tinted base. By 1969, the Ivory tinted paper was no longer sold in the Bromide range of papers, although Kodak continued to make Bromesko Ivory Fine Lustre paper until the mid 1970s.  |

| Bromesko Instruction Sheets; 1947, 1950 and 1953 | |

|

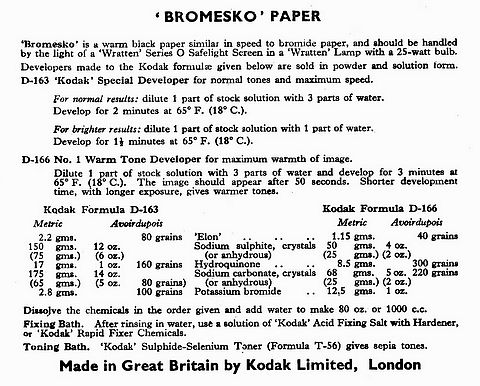

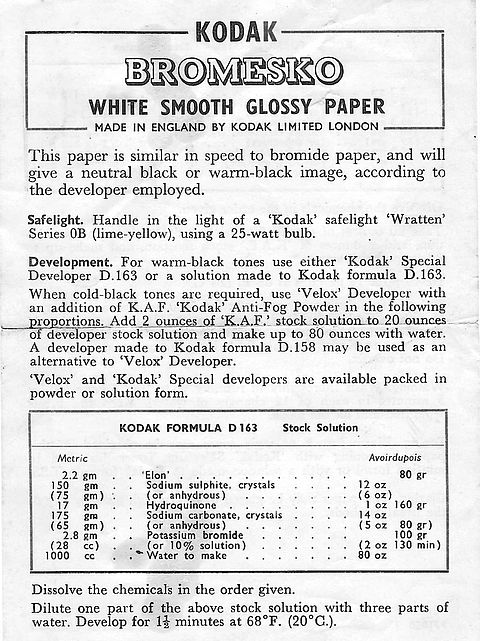

February 1947 instruction sheet, left. This instruction sheet suggests that the paper should be handled under a Wratten Safelight filter Series 0, (Orange). Series 0 was replaced by Wratten Series OB in 1950 (see the 1950 instruction sheet, below). Kodak formula D-166 could be made up to the formula given for maximum warmth in image tone. By the early 1950s, this developer was being sold as a packaged chemical named “Kodak Extra Warm Tone Developer” put up as a powder. It was also available in solution form sold in 8 fluid ounce bottles.

October 1950 instruction sheet, below, left and right. |

|

|

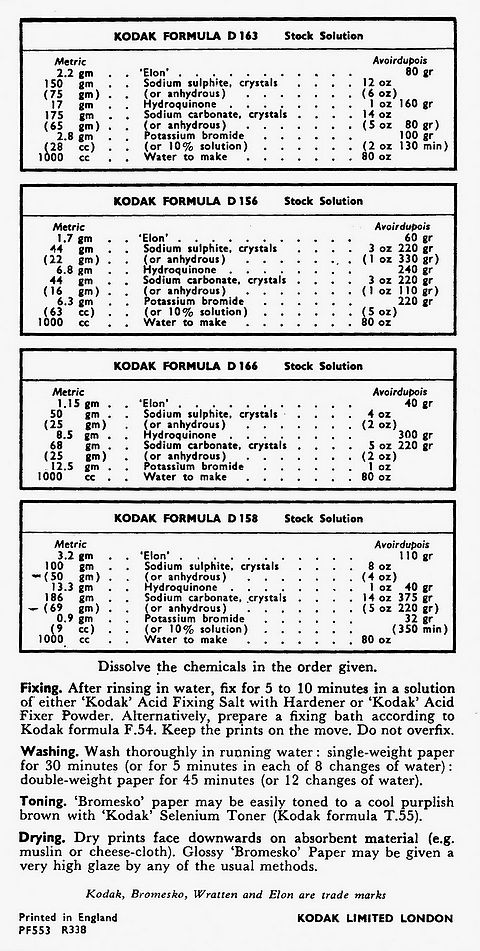

| May 1953 instruction sheet, below, left and right. | |

|

|

|

The middle box with the early type of sealing label dates from 1959 to approximately 1961. The Postcard boxes of Bromesko paper (left and right hand sides) with the new design of sealing label date from 1961 to 1965. The left hand box contained Bromesko paper with a 'Cream' paper base colour. Cream Fine Lustre, Normal, Doubleweight. 'Cream' was of a reddish brown colour, and gave a very warm toned print with a brown black. 'Cream' based paper was most suitable for portraits and summer landscapes. Kodak (UK) discontinued making Cream base paper in 1967. |

|

| Bromesko Instruction Sheet; 1964 | |

|

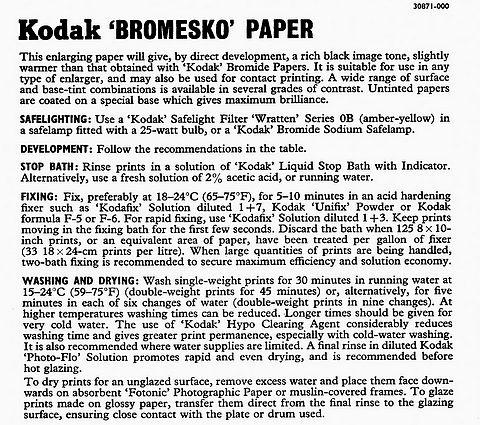

By 1964 it was unusual for photographers or printers to make up their own solutions from raw chemicals and the formulae for D-156 and D-166 and their corresponding packaged products were no longer in use, although 'Royal Bromesko' liquid developer, introduced in 1963, may have been based on the formula for 'Extra Warm Tone' liquid developer. At this time, October 1964, Bromesko was still available in a 'Cream' base paper, adding much to make the print appear sepia toned. Kodak withdrew 'Cream Fine Lustre' paper in 1968, although manufacture of 'Ivory Fine Lustre' continued until 1977. References to above Bromesko

instruction sheets: Kodak catalogue Section 4, Kodak Photographic

Chemicals, January 1953. NOTE: All instruction sheets are downloadable as pds from this section. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

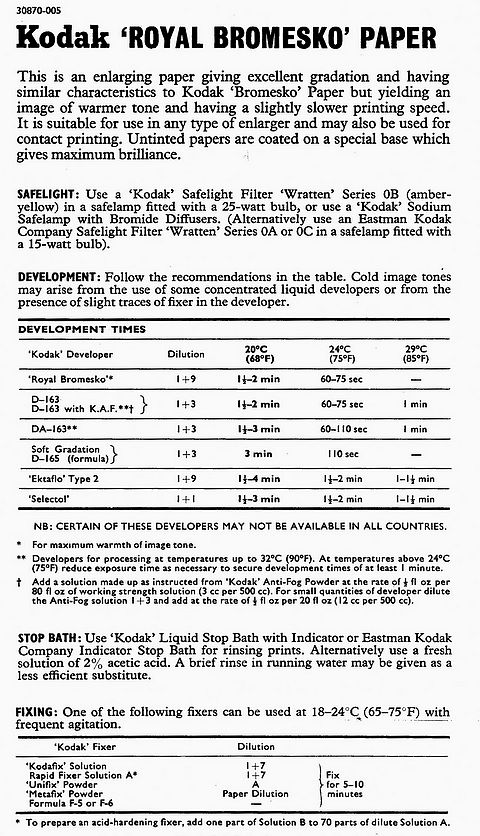

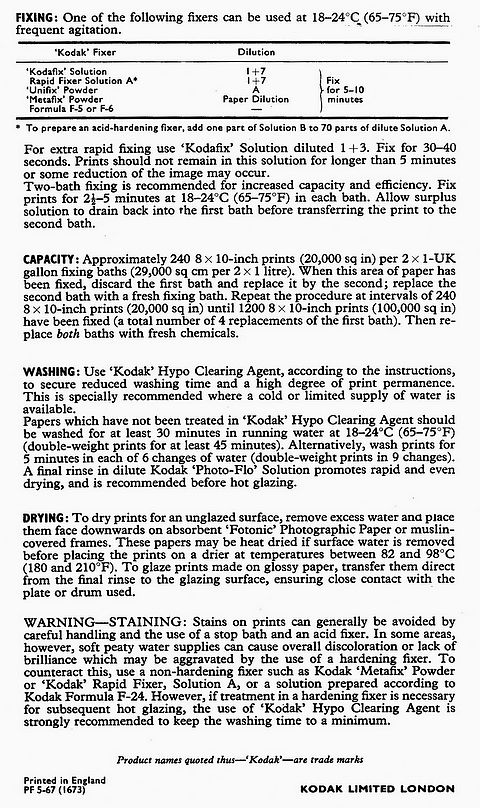

Royal bromesko paper was introduced in 1962 and discontinued in 1977. It was available with 'Smooth Lustre' and 'Fine Pearl' surfaces with a choice of a white or ivory base in Double Weight only. Types of Royal Bromesko

Paper from 1962. In July 1962, the paper was

initially sold as a “Special Order” item, and the minimum

order accepted was for 1000 square feet in area of any one contrast

grade and size. White Fine Pearl (WFP) and

Ivory Fine Pearl (IFP) surfaces additionally became obtainable

during 1962 to ’63, and the paper was no longer sold as

“Special Order”. Sizes and quantities were listed in

the UK Kodak Professional Catalogue for 1963 in the Bromesko

paper section, from 3½ x 4½ inches to 16 x 20 inches,

10, 25 and 100 sheet packs, in the three contrast grades noted

above in Double Weight base. Fine Pearl was a new surface in 1962. It had a matt surface with an extremely fine grain. Kodak recommended this surface as a good choice if much retouching had to be done to the print, as in portraits. Ivory Smooth Lustre surface

(ISL) had originally been introduced in the late 1950s as a Bromesko

paper. In 1959 it was for sale in mainly continental sizes. Another surface listed under “Bromesko” paper in the early 1960s was White Fine Low Lustre. The author believes this surface was very similar or identical to Fine Pearl. Both surfaces are listed for sale in the “Kodak Professional Catalogue” for July 1964, Low Lustre as a Bromesko paper, Fine Pearl as a Royal Bromesko paper. A list of Kodak black and white printing papers dated October 1965, however, does not mention the Low Lustre paper. Royal Bromesko surfaces

added in 1965. By 1969 the Smooth Glossy and Fine Lustre surfaces had been discontinued along with the Ivory Smooth Lustre surface. A year or so later the Ivory Fine Pearl surface was no longer made leaving White Fine Pearl, WFP and White Smooth Lustre, WSL in Soft, Normal and Hard grades. Royal Bromesko gave a warmer image tone by direct development in Kodak D-163 developer than Bromesko paper processed in the same developer. For maximum warmth, Kodak “Royal Bromesko” developer produced an almost brown and white image. Royal Bromesko Developer was obtainable in liquid form, to be diluted one part developer to nine parts water, to make a working solution for use with Royal Bromesko paper. Also, in powder form, Kodak “Warm Tone Developer” was available in the 1960s, the stock solution to be diluted one part developer to one part water for a medium warmth of tone.It had a slightly lower printing speed than Kodak Bromide or Bromesko papers. Royal Bromesko could be processed under a Wratten Safelight filter Series OB (and subsequently also Series OA and OC). The author purchased a box of Royal Bromesko paper, 6½ x 8½ inches, 100 sheets, in White Smooth Lustre surface, Grade 3, in 1968 (WSL 3D). The difference in image tone between Royal Bromesko and Bromesko papers was very noticeable, even when processed in the standard Kodak paper developer, D-163. The author found, when comparing prints for contrast and density, that the visual contrast decreased on Royal Bromesko because of the colour of the image compared to a similar print made from the same negative on Kodak Bromide paper. The blacks of the print turned brown-black and mid tones a light brown. He found Royal Bromesko paper difficult to use and many people preferred a “good black” as reproduced on a Bromide print to a rather insipid brown black on a Royal Bromesko print. Warm tones on Ilford “Clorona” paper were popular in the 1930s. The Ilford Manual for 1935 gives two print developers, ID-23 and ID-24, suitable for producing warm-black to sepia to red tones on Clorona paper. The Ilford Manual stated that Clorona paper required a negative of “Fair contrast” when brown-sepia to red tones were desired. As the tone of the print changed from brown-black to sepia, and finally to red, the visual contrast decreased, so that a negative of fairly high contrast usually gave the best results. This is exactly what the author found when using Royal Bromesko paper. |

|||

| Below is shown an early leaflet for Royal Bromesko paper dating from August 1962. Initially introduced in a "Smooth Lustre" surface (White and Ivory), another surface, "Fine Pearl", was available by early 1963. | |||

|

|

||

|

Instructions for Bromesko Royal Paper, May 1967 References: Kodak Professional catalogues, 1966, 1968; Kodak dealer catalogue, 1965. |

|||

|

|

||

| Royal Bromesko Packaging 1962 to mid-1970s | |||

.jpg) .jpg) |

.jpg) |

||

.jpg) .jpg) |

.jpg) .jpg) |

||

|

.jpg) |

||

|

|

|

|

Click on the following titles to download the files as pdfs Bromide Paper,

1938; Bromide Paper 1944; Bromide Paper 1945-47 (estimate); Bromide Paper, October 1952; Bromide Paper, July 1957; Bromide Paper, 1964; Bromide Paper, April 1967 |

|

|

|||

|

History of Kodak Bromide

Transferotype Paper 1923 1933 1940 1957 1960 to 1964 “Normal” contrast only. 8 x 10 inches sheets and 40 inch x 33 feet long rolls. Other sizes to special order. 1965 As far as is known, Eastman Kodak at Rochester, USA, never manufactured a photographic paper of this type. Transferotype Bromide paper

had an emulsion which could be transferred onto an opaque or

transparent surface. The paper was exposed in exactly the same

way as a normal Bromide paper and then developed in a suitable

black and white print developer such as Kodak D-163, diluted

1 part developer to 3 parts water. Development time was 1½

minutes at 68°F (20°C). Kodak “Universal”,

a concentrated liquid developer. Print developers designed for use with chloro-bromide papers, or “warm tone” papers, such as Kodak “Bromesko”, were not recommended. It was essential to use a non-hardening

fixer with Transferotype. Prints were washed after fixing

for about 30 minutes, and could be transferred immediately or

dried for future use. Heat drying was not recommended. Wood, cloth, pottery, metal, or interior plaster board were suitable surfaces for receiving the photographic image printed on the Transferotype paper. Translucent or transparent surfaces also gave good results, but about four times the normal print exposure was necessary before transferring onto a transparent surface. This was required to give enough density to the print when light was projected through the image as opposed to light reflected from the image. Transfering the Image

from Paper to Support The support, with it’s

gelatine coating, was then hardened in a Chrome Alum hardening

bath for about 5 minutes, then washed for 10 minutes

before drying. After drying, the print and it’s support were soaked in water and squeegeed together with a roller face to face, the front of the print facing the support. The “pack” was kept under pressure between photographic blotting paper for at least an hour. To complete the transfer, the print and it’s intended support were immersed in water at a temperature of 100°F to 105°F until the print base, the paper which the photographic emulsion was coated onto in the first place, came away from the intended support. For transfer onto a hard surface, such as glass to make a black and white transparency, a higher temperature at 130°F to 160°F was necessary. After transfer, the transferred print on its new support backing, were treated in a Hardening Bath of 2% Chrome Alum and washed for a few minutes before drying. Since the front surface of

the print is placed onto the front surface of the support, the

back of the print is then facing you. Consequently, the resulting

transferred image is reversed, left to right. To avoid this,

the negative had to be placed emulsion side up in the enlarger

negative carrier, so as to make a reversed Transferotype print.

After it was transferred, of course, it appeared correct. Safelight Kodak suitable safelight filters: 1940s and 1950s Wratten Series OA in the 1940s; this became Wratten Series OB from 1953 and was recommended for all Kodak safelamps. |

|||

|

Note the original price of this 10sheets packet = 7/2 = 7s & 2d = 36p (new pence). D-170 was an “Amidol” type of print developer, made up to the Kodak formula. D-170 was never sold as a Kodak packaged product. |

||

|

|

|||

|

Finisher Bromide paper was

made with a surface specially for re-touching. The description

given in the 1933 Kodak UK catalogue reads: The paper sample taken from the packet shows a surface with slight reflectance and very slight roughness. It could be described as a semi-matt surface with a very slight fine grain appearance. According to the 1933 Kodak UK catalogue, the paper was obtainable in single weight and double weight thicknesses, in soft, medium, and contrast grades. Apparently it was first marketed in the early 1930s, certainly by 1933, but was no longer manufactured after 1946, with no equivalent surface within Kodak's new range of papers introduced in 1946. 'Tooth' in re-touching terms refers to the roughness of the paper surface. This surface roughness gives something for the re-touching medium to penetrate into and 'key' onto. A print made on ordinary glossy paper would be difficult to re-touch as the re-touching medium, whether pencil, crayon, or liquid colourant (ink or dye) applied by brush, would leave an obvious surface mark in the case of pencil or crayon, and would likely smear in the case of liquid retouching. The 'tooth' surface enabled the re-touching medium to penetrate into the surface and be far less visually obvious. |

|||

|

Above is shown a 100 sheet box of Finisher paper, of postcard size, 3½ x 5½ inches, medium grade and double weight. There is no code printed on the label but it could be assumed to be BF-2Z (Z = double weight). medium grade in single weight. Code BF-2, Bromide Finisher grade 2. Possible price is two shillings and sixpence (2s/6d = 22½p). |

||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flammable Nitrate to Acetate Safety Film Base (notes taken from an 'Enquiry Desk' answer prepared by Rex Hayman; Amateur Photographer, 3rd December 1969.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Under certain circumstances, it is possible for nitrate-based film in poor condition to spontaneously ignite. The hazard of a large quantity would be considerable and the fire difficult to extinguish. In 1948, cellulose triacetate was introduced and, due to its improved "bending"properties, it was adopted for professional motion picture films. By about 1951-52, the major film manufacturers had ceased to produce general purpose nitrate-based films. . If you are storing any old professional cine films you should establish what they are as quickly as possible. Identification of the base material is relatively straightforward. Most films have such information printed in the margins and, if the word "nitrate" appears, the material should be treated with caution. Should the margins be blank it is best to assume that the base is cellulose nitrate. Occasionally confusion may arise when the word "nitrate" appears in the margin of a duplicate film made on modern safety materials, but this is usually due to the word being transferred from the margins of the original film during copying. Motion picture film was not the only material to use a nitrate base. For many years roll films and 35mm films were also coated on to this and therefore anyone possessing a quantity of pre-1945 negatives should exercise caution. The last known use for nitrate-based roll film was about 1950. Small-gauge cine films are probably the safest. Kodak, especially, have not produced a 16 or 8mm film for amateur use on anything other than a safety base, and this is always indicated along the margins with the printed words "safety film" throughout its entire length. If identification of the base material proves difficult and any doubt exists, play safe and assume it is not safety film. It is not unknown for nitrate-based film to remain in perfect condition for 50-60 years, whilst there are also instances of rapid deterioration after only a few years of storage under poor conditions. For some time it was considered that processing inefficiency was a contributory factor to its life span, but this has since been disproved. It is not easy to recognise symptoms of deterioration very early, as these can appear totally unexpectedly and very rapidly, temperature playing a big part in this. In an advanced state of deterioration, the film image is destroyed and the film turns yellow and then brown, ending finally as a grey powder. Ignition normally takes place at a reasonably high temperature, say 300°F (150°C) but it has also been known to occur in a film storage 'can' at only about 100°F (40°C). Toxic fumes are given off also, and if moisture or damp is present, nitric acid may form. Although acetate bases were available between the wars, these early versions would not stand up to hard and continuous wear, making them especially unsuitable for motion picture film. However, with the introduction of a base made from high acetyl cellulose acetate (cellulose triacetate), "Safety Film" became universal. Although these are not strictly non-inflammable, they are slow burning. If you consider that a quantity of film in your possession is on a nitrate base and any sign of decay or ageing is visible, keep it cool and dry, and notify the Fire Prevention Officer at your local fire station. Do not attempt to destroy it yourself. Incidentally, the major film manufacturers are now considering dropping the marginal print "Safety Film" as it can be assumed that all modern film is 'safe'. Further

on this subject comes

from the book 'Silver by the Ton, a History of Ilford Ltd,

1879-1979'; ISBN 0-07-084525-5. This was soon extended to graphic arts films, motion picture film, miniature films and, finally, to roll film, though note that Rex Hayman, above, suggests this change-over was not complete until 1948, with no doubt WW2 intervening to slow down the universal adoption of acetate base. The final paragraph (below) suggests it would have been post-1946 in the UK. This move, forced by safety

considerations, was soon turned to a sales advantage because

cellulose acetate, especially when coated with Saran resin to

improve its water-resistant properties, proved an Soon after WW2 ended (in Europe; 8th May 1945), the whole (Ilford) company closed from Saturday, August 4th to the morning of Wednesday, 8th August 1945. Almost at once negotiations with BX Plastics Limited reached fruition over the creation of a joint company to produce triacetate film base. Bexford Limited was formed, a liaison name derived from the two names of the parent companies. Its creation had been helped by the Ministry of Supply when film base was very difficult to obtain from the USA. Production started in 1946. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Film Introduction Dates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The followiwng table applies

to UK made film only. Some of the Eastman Kodak USA equivalent

films were introduced at different times.

Tri-X sheet film was introduced in 1939 but was not made in any other format until 1955, when it became available in the USA as 35mm, 120, 127, 620, and 828, though not at first in the UK, even as late as November 1955 (Ref; Camera World, p302). It was announced in the BJPA for 1956 for the UK market. Verichrome Pan also first appeared in the UK in 1956. Initially at 80ASA, it went up to 125ASA when the speed 'Safety Factor' was removed in 1960. The name Panatomic-X

was retained from its first use in 1938, but in 1956 it was a

new emulsion, speed rated at 25 ASA daylight & 20 ASA

tungsten (40 ASA

from mid-1960), matching the quality of the new Tri-X and

Verichrome Pan films (Re; BJPA 1957, p210). In brief, this reads: Super-Panchro Press sheet film, still available in 1954, gave way to Panchro-Royal sheet film in 1955. Royal-X Pan, in 120 roll film format only and with a light sensitivity 4x that of Tri-X. It was hailed as "the world's fastest film" when it was first advertised by Kodak in the BJPA for 1959, suggesting it may have first gone onto sale in 1958. In the USA in 1960 (uncertain; 1956-1961), Plus-X Pan Professional film was available in 120 and 620 roll films, but you had to buy a minimum quantity of 25 rolls at a time. In the UK in 1963, Plus-X roll film was reinstated as Plus-X Pan Professional film in 120 size rolls. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Film Speed 'Safety Factor' in the 1930s (until

mid-1960) Professional photographers who worked out their own exposure times using exposure meters or by other reliable means and who developed their own films, could double the speed printed on the film carton with little danger of under exposure. Plus X 35mm film could be exposed at 125 ASA(ISO) or 32 Kodak, and Super XX 35mm or roll film at 250 ASA(ISO) or 35 Kodak. This increase in speed was only successful when the films were developed in a developer which did not decrease the film speed during development; best would have been something like Kodak D-76 developer. Developers labelled “Extra Fine Grain” often cut the film speed down by about half a stop, some as much as one stop, halving the ASA(ISO) rating. In the summer of 1960, manufacturers removed the above safety factor (only relevant to black & white film), as can be read here. A Kodak Leaflet from May 1961, entitled 'What's happening to film speeds?', which explains why Kodak increased the speed of their black & white films, can be downloaded as a pdf here. On the last page (p6) is a list of films and plates, together with their revised speed ratings, as available from Kodak at that time. This leaflet was a continuation of an article published 6 months earlier in 'Kodak Professional News' magazine for December 1960. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Below are two pictures from a Kodak booklet “How to take pictures at night” published in 1937. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plus-X Roll Film A Kodak catalogue for films, dated January 1954, and a May 1952 price list which came with it, lists the interesting Plus-X roll film, which was only on the market for about five years – 1951 to 1956. It was replaced by Verichrome Pan in 1956. Pre-1956, Verichrome film (since Spring 1931) was not Panchromatic but Orthochromatic i.e. insensitive to red light. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Plus-X

Pan Professional Roll Film in multi-film packs In the USA, Plus-X Pan Professional was available in 120 and 620 roll films from 1960 (uncertain; 1956-1961), but you had to buy a minimum quantity of 25 rolls at a time. Prior to June 1963, Eastman Kodak seemingly speed rated the USA Plus-X Pan Professional at 160 ASA, as evidenced by an item within the 'Tech Section' of the American magazine 'Popular Photography', dated August 1963. 'Tech Section' contained a column entitled 'Facts, Ideas, Hopes' written by William J. Sumits, 'Chief, Life Photographic Laboratory', presumably meaning he was Chief of the now defunct Life Magazine’s Photographic Laboratory. Mr. Sumits reported that they (presumably the people at Life Magazine), had been recommending for over a year that photographers should rate Plus-X film at 125 ASA instead of Eastman Kodaks’ rating of 160 ASA. The reason being that, when printing Plus-X negatives rated at 160 ASA, the negatives were too contrasty to print well on condenser enlargers. Not long afterwards, Eastman Kodak changed their official speed rating of Plus-X to 125 ASA for all formats. This lower speed was applied to the UK Plus-X Pan Professional from its August 1963 introduction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The pack of Plus-X Professional shown below has a “Dev. Before” date of January 1971.

Plus X Pan Professional film instruction sheet shown to the right. This instruction sheet was enclosed in a pack of ten 120 roll films with a 'develop before' date of January 1968. The instruction sheet is dated September 1965. As Plus X was a 'fast developing' film, it was recommended to use the diluted form of D-76 developer for more control of contrast and density. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Instruction Sheet for Panatomic-X, Plus-X and

Super-XX 35mm Films Below is a UK instruction sheet (both sides) for Panatomic-X, Plus-X and Super-XX as 35mm films. It is believed to date in the range 1938-1940. It gives much information on these three, then new, films. It was possibly packaged within each 35mm film box. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Super-XX 35mm film in the UK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Super-XX 35mm film was introduced in the UK in 1938. At that time it was the fastest film made by Kodak UK and rated at a speed of '32 Kodak' to daylight or '30 Kodak to tungsten lighting. An article published in the Wallace Heaton 'Minitography and Cinetography' catalogue of 1939 (which eventually became their well known "Blue Book") written by E.R. Davies, the Director of research for Kodak UK, gives much information on Super-XX film plus two other films, Plus X and Panatomic X, both introduced at the same time. It was said Super-XX film possessed a finer grain structure than Super-X, the fastest film prior to 1938. Super-X was replaced by Plus-X in 1938. A Kodak leaflet printed at the time of the introduction of the films, or slightly later, describes the films and includes development times. 32 Kodak speed was approximately 125 ISO/ASA and the tungsten speed of 30 Kodak was approximately 80 ISO/ASA. In the late 1940s the film speed was decreased to 31 Kodak or 100 ISO/ASA to daylight. The film speed may have been decreased due to a reassessment of film speeds when the ASA system of film speeds was introduced in 1946. In 1952, Super-XX film was available in 36 exposure cassettes, tins of bulk film in 1.6, 5 and 25 metre lengths for cassette loading in the darkroom. Size 828 rollfilm for Kodak 'Bantam' cameras was also obtainable. The film was coded 'XX' and a 35mm cassette of 36 exposures (XX135) cost 9shillings and 5pence (9s.5d); about 47p. In 1953 the 35mm film was described as "A modern type of high speed panchromatic film combining extreme speed with a degree of fineness of grain which meets all normal requirements in enlarging……………..a very long exposure scale and wide latitude in exposure. Colour sensitizing is panchromatic without exaggerated red sensitivity. Soft gradation. For high speed and artificial (light) work of all kinds. Press photography, news reporting, action, night and indoor subjects". Kodak increased the speed of the 35mm film to 160 ISO/ASA for daylight exposures and 100 ISO/ASA for tungsten lighting, in 1954. These speeds had a 'Safety Factor' built in of one stop in exposure. Hence, experienced photographers could expose their films at double these speeds without under exposing. Tri-X film replaced Super-XX in 1955 in 35mm and all roll film formats. Tri-X 35mm and roll films were included in a 'Kodak Dealers' catalogue printed in December 1955. Although Tri-X replaced Super-XX, it was still possible to purchase Super-XX film in 36 exposure cassettes and bulk film in 1956 while 'stocks last'. It sold at a reduced price compared to the new Tri-X. The 'Kodak Professional' catalogue for 1957 only listed the sheet film version of Super-XX. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Super-XX 35mm and Roll Film in the USA and Transition to Tri-X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The 35mm size of Super XX film was introduced to the US market in 1938. The film had a 'Kodak' speed of 320 to daylight and 200 to tungsten light. Another speed rating given in a table of film speeds for American films in 1941 was the G.E. (General Electric) speed rating system, which gave 100 for daylight and 64 for tungsten. Although films were not yet rated by the ASA (American Standard Exposure Indexes) the G.E. speeds corresponded almost exactly to the ASA speed. A data sheet from March 1945 described the film as “very high speed for indoor and outdoor use under adverse lighting conditions and where very fast shutter speeds are necessary”. Kodak D-76 was the recommended developer for general use at developing times of 16 minutes for dish development with continuous agitation, or 20 minutes tank development with intermittent agitation at 68°F. Exposures could be reduced to a minimum by doubling the film speed to 200 ISO/ASA in daylight. Cassettes were available in 18 or 36 exposures coded XX135, plus bulk 35mm film in lengths of 27½, 50, 100, and 200 feet for darkroom loading into cassettes. Super-XX was also obtainable in 828 roll film for 8 exposures, coded XX828. By 1952, 20 exposure cassettes replaced the 18 exposure and by then the film was also manufactured in bulk rolls of 70mm. The sensitivity of the film was known as “Panchromatic Type B” which meant that most subjects taken in daylight reproduced the correct tone of grey in the print. The emulsions used in Type C panchromatic films were slightly over sensitized to red light, making them more suitable for exposures under tungsten lighting. By 1953, Eastman Kodak no longer included the 'sensitizing class' in their film data sheets. Tri-X sheet film had been on the US market since 1939, but in 1954 Eastman Kodak introduced Tri-X 35mm film and various sizes of roll film with a speed of 200 ISO/ASA to daylight. This speed included a safety factor of at least one stop, and most photographers found they could double this speed to 400 ISO/ASA (when the film was developed in D-76) for the best quality negatives. Even higher ratings were possible in other developers, such as DK-50, or DK-60a, where Tri-X could be exposed at 800 ISO/ASA for press or 'available light' photography. The first data sheet for Tri-X in 35mm and roll film formats was published as an 'insert' in an Eastman Kodak booklet entitled “Kodak Films”, dated May 1955, where the data sheets for Super-XX 35mm and roll films were also included. In the data sheet, Kodak Tri-X film was described as “A very fast film of moderate graininess for indoor and outdoor use under adverse lighting conditions. It is especially valuable for photography by existing light at low levels of illumination, as well as for work where high shutter speeds are required.” By 1957 Tri-X films had replaced the Super-XX films apart from Super-XX sheet film. In the next edition of 'Kodak Films', published in January 1958, only the data sheet for Super-XX sheet film was included. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Courtesy of Alan Douglas of Pennsylvania, USA, the picture to the left shows three 35mm cassettes of Super-XX film, found in a travelling trunk used by his late father. The cassettes are believed to date to the 1940s, which corresponds well with the following notes based upon a Wikipedia article. Super-XX was Kodak's standard high-speed film from 1940 to 1954, at which date Tri-X was introduced in similar formats. Tri-X was twice as fast with finer grain. Super-XX is believed to have been phased out in 1960. When first placed on the market it was speed rated at 100 ASA (ISO) and was discontinued in roll and 35mm formats around the time of the general speed increase that applied to all monochrome films, and would have increased Super-XX to 200 ISO, due to the exposure safety factor being reduced. It had a relatively coarse grain, with a very long, almost perfectly straight-line, characteristic curve. Its great exposure latitude made it ideal for variable development techniques, both longer and shorter. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Verichrome, Plus-X Pan Professional and Tri-X Pan Roll Films | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the left are two rolls of

Verichrome Pan roll film, the top dated “Develop Before

August 1960”, and the bottom, “Develop Before November

1964.” In 1952 Verichrome film was sold in 8 roll film sizes, the largest being 122 size, which produced a negative of 3¼ x 5½ inches, 6 exposure to one roll of film. Film speed was 50ASA (ISO) to daylight but, because of its insensitivity to red light, the speed dropped to 25ASA (ISO) in artificial (tungsten) light. As far as can be ascertained, Kodak Verichrome film was first sold, in some format or another, as long ago as 1930. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Verichrome Pan 120 roll film shown below was made in the USA by Eastman Kodak and is interesting because it seems the speed rating in ASA has been stamped onto the carton instead of the usual printing. This may be because, at the time of its manufacture i.e about December 1962, the ASA speeds were being doubled to eliminate the “Safety Factor”. The speed of all sizes of Verichrome Pan films was increased from 80 ASA (ISO) to 125 ASA (ISO) in 1960 to 1961. To the right is the instruction leaflet that accompanied the film in the carton below. These are dated March 1962 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Verichrome Pan film had a very fine grain emulsion and was sensitive to all colours. It was a general purpose film with a very wide exposure and development latitude, making it popular for amateur photographers, author included. In 1955, Verichrome Pan and Plus-X 35mm film were both rated at 80ASA (ISO) until 1960, when the speed was doubled (no change to the film) to 160 ASA (ISO) for Plus X and 125 ASA (ISO) for Verichrome Pan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|